A Tale Of One City And Two Henry Smiths

These London landlords are separated by four centuries — but are joined by a common name, business interests, and concerns about their legacy.

London Centric will be back in its normal form next week – please do send in any stories you think we should be investigating. But for now, as we enter a new year, we bring you something a little different as a one-off.

This is a story that spans 450 years, based on historical documents, court judgments, and original on-the-ground reporting about two Londons, past and present, inhabited by two Londoners called Henry Smith.

London, 2026

Henry Smith is a London landlord and sometime money lender. Through a series of canny land deals he has built a great fortune, surfing a wave of change in the capital to his personal benefit.

For decades he has worked hard to build up his business from a base on the northern fringes of the City of London, surviving the tumult of the great financial crisis to thrive. A natural deal maker, he recognises that bold gambles on buying land are what underpin many of the capital’s greatest fortunes. He is involved in high-profile philanthropic endeavours, and he’s not afraid to put himself and his name at the heart of them.

The details of the 63-year-old’s business interests are well documented, sometimes to his annoyance. In addition to the property developments across London there’s the collapsed payday loans company, a mass eviction of his tenants last Christmas, and now, London Centric can reveal, the potential unlawful operation of a student housing project in Deptford.

What’s more, we have learned many of the people he evicted 12 months ago have hit back and won multiple victories — receiving substantial payouts from Smith’s company after it failed to correctly protect their deposits or licence their homes with the local council.

His is a very London story.

London, 1627

Henry Smith was a London landlord and money lender. Through a series of canny land deals over several decades he built a great fortune, surfing a wave of change in the capital during the Jacobean and Elizabethan eras to substantial personal benefit – with his actions suggesting a deep concern for his legacy and public profile.

For decades he worked hard to build up his business, from a base on the northern fringes of the City of London, surviving the religious tumult of the Elizabethan and Jacobean ages. A deal maker, he was not afraid to put himself at the heart of his philanthropic endeavours. He recognised that bold gambles on buying land are what underpin many of the capital’s greatest fortunes.

Housebound in his old age, he spent his time in his substantial property on Silver Street, a few doors down from the former lodgings of William Shakespeare and close to the future site of the Barbican. Described as “weak and infirm in body by a great rupture and being hard of hearing”, Henry Smith set about cementing his legacy with a detailed will that formed a charity to distribute his wealth in a very precise manner.

He would never have imagined that hundreds of years later his decisions on that deathbed would continue to shape modern London – not only in terms of the layout of the city but also due to a charitable endowment that gives large lump sums to some of its residents and causes.

Among the beneficiaries are thousands of his descendants, traced down through modern ancestry software, who through a happy accident of birth are still able to apply for a portion of his spoils in times of financial need.

His is a very London story.

Deptford, 2024

It’s December and London Centric is on Childers Street in south east London. The 21st-century Henry Smith has just issued no-fault eviction notices to every resident of his company’s Vive Living development in Deptford during the festive season. The development had promised to offer long-term private rental security to young professionals. Instead, 150 residents have been suddenly told they were being kicked out by Smith’s Aitch Group and given two months to find a new home.

The email informing them they were to be made homeless was sent from a company account that signed off with the email signature “Merry Christmas”.

For a few weeks Smith is one of the city’s public villains, the ultimate face of the uncaring London landlord. London Centric spent several days down at the site, talking to residents who had been sold a promise of secure private rental living and who were instead left homeless.

Maryam, one of those evicted, told us about the mental impact of being turfed out through no fault of her own: “All of us, we were working professionals, we’re paying our rent and paying our taxes. We were not criminals. We were just people, families, kids.”

But the tenants won’t go down without a fight. Instead, with the help of their local MP, council, and renters’ rights groups they manage to be a very expensive pain for Smith’s company — forcing him to make substantial payouts to tenants due to a failure to abide by basic rental laws.

Wandsworth, 1548

The 16th-century Henry Smith first came on to London Centric’s radar while we were trying to research his modern namesake. Every time we tried to dig into corporate or charitable records involving the modern day property developer and money lender, we kept encountering equivalent accounts of the Henry Smith who preceded him in the same lines of business, in the same areas of the capital, by 400 years.

The more we dug, the more we were intrigued by an Elizabethan businessman whose actions shaped, and continue to shape, modern London.

The historic Henry Smith was a man of dubious morals. From a landed gentry family that had fallen on hard times, he was born in a tiny village called Wandsworth where his family owned linen mills that flourished on the banks of the fast-flowing Wandle river.

He moved to the City of London, to the parish of St-Dunstan-in-The-East by the Tower of London, then entered the money lending business, benefitting from the financial chaos following the dissolution of the monasteries.

According to Lucy Lethbridge and Tim Wales, his biographers, Smith was a “prickly and controlling type” known for driving a hard bargain. His contemporaries seem to have had little love for him, as he grew his fortune rapidly accumulating land by buying foreclosed mortgages.

Smith was a “shrewd and often ruthless businessman, a moneylender, and a property speculator”, according to his biographers. After starting as an iron merchant he developed a specialism as “a fixer for impoverished aristocrats” who needed money. This brought him into the circle of the profligate aristocracy, dealing with the religious to-and-fro of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras.

In a religious age where money lending was frowned upon, Smith presented himself as a puritan interested in philanthropy but saw the opportunity to make a large return from others who needed cash. One deal resulted in him owning Knole, a giant country house on the edge of Sevenoaks which is now in the possession of the National Trust.

It was money lending and locking in those unable to pay their debts to preserve his legacy that fixated Smith in his final years.

London, 2016

The 21st-century Henry Smith is in trouble. He and his family are all over the newspapers as the unacceptable face of capitalism following a disastrous move into the payday loans business.

Until now he had stayed largely under the radar, having clawed his way up from the East End through sales jobs and then founding Aitch Group to develop property in London and the south east, before moving to Knightsbridge. His special tactic, according to a podcast interview, is taking the risk of buying land at a discount before planning permission is achieved.

But the media and financial regulators have begun to take an interest in another arm of his business empire. Since 2008 he has invested £8m in a payday loans company called CFO Lending, during the era when the likes of Wonga were expanding fast. It lent modest sums of money at high interest rates to some of the poorest in society and from the very start, the financial regulator later found, it was engaged in sharp practices.

While Smith drove Ferraris with his wife around Europe, his payday loans company was taking money without customer permission, sending threatening messages, and failing to check whether customers could afford their loans.

The Guardian reports how a student was lent money by CFO Lending at an interest rate of 16,734,509%, prompting criticism from Labour MP Stella Creasy. Another woman is left with “very serious distress and inconvenience, including damage to her mental health” due to the lender’s actions.

The firm is eventually put into administration after the Financial Conduct Authority criticised “serious failings” that “caused detriment to many customers”. CFO Lending is told to write down or reduce £32m of existing loans and pay back £2.9m to 97,000 customers over “unfair practices”.

Silver Street, London, 1627

The historic Henry Smith married a woman whose name is not recorded but never had children. He appeared to have spent his efforts climbing the political and social ladder of London, through the Salters company and becoming an alderman of the City of London. In his final years he was fixated on how he would be remembered, how his money would be spent, and how to ensure his death would not enable his debtors to escape repaying their money.

At one point, in his mid-70s, he feared his fortune was slipping away from him when the young Earl of Dorset, who owed him £9,000, died following a series of illnesses, attributed by one contemporary to the consumption of a “surfeit of potatoes”.

Henry, hard of hearing and housebound, pressed on with setting out his meticulously detailed instructions for where his money should go. Trustees would be appointed to ensure the debts he was owed would still be repaid after his death. Sums were donated, both before and after his death, to specific towns.

Many were Surrey towns that would later be swallowed up by the capital and become the south west parts of Greater London. Croydon, Kingston, Richmond, and Wandsworth are among the places that benefitted from his largess and in some sense benefited from his early investment.

Other money was set aside for the poor, on the condition they were not heavy drinkers, “whoremongers, common swearers, pilferers, or otherwise notoriously scandalous”.

Most intriguingly, Smith set aside £1,000 (the equivalent of £230,000 today) to provide for any direct descendants of his sister Joane who fell on hard times, known as the poor “kindred”.

After his death the charity’s trustees decided to buy 86 acres of farmland with this money, in the hope that the modest rent of £130-a-year would then provide income to distribute to these impoverished descendants. The open fields they purchased were to the west of London around the sleepy undeveloped village of Brompton — the future site of South Kensington.

London, 2016

The modern day Henry Smith is still having a bad time. The Daily Mail is criticising his family under the headline: “The East End payday loan tycoon and his VERY glamorous girls: Lavish lifestyle of the jet-set family behind a ‘parasitic’ lending company.” The Times went with “Lender threatened victims while family lived high life”.

His wife and three daughters sat on the board of CFO Lending, although there was no suggestion they were directly involved in any wrongdoing. They stood down shortly after the financial regulator launched an investigation, later accepting a temporary ban from serving as company directors.

One of his daughters, Brogan Garrit-Smith, had posted pictures of her life travelling the world on private jets, along with her dog. In one post she said: “I enjoy the simple things in life like recklessly spending my cash and being a disappointment to my family.”

Kensington, 1873

The small marshy village of Brompton, bought on the cheap by the trustees of Henry Smith’s Charity in the 17th century, had become a core part of booming west London by the Victorian era.

The charity began to develop the land it owned between Fulham Road and Old Brompton Road into the area around modern South Kensington tube station. The open fields, once rented out for a pittance as farmland to grow salad, became the site of some of London’s most in-demand housing, massively increasing the charity’s income. Onslow Square, Pelham Crescent, and Thurloe Square — opposite the Victoria and Albert Museum — are all built on the charity’s land.

During this era the legend of the mysterious 16th-century Henry Smith continued to grow in line with the fortune of his charity, as people sought to understand the motivation behind the man who left the pot of money that was exploding in value.

In 1873 Charles Dickens Jr, the somewhat less famous son of the writer, documented a well known myth that Henry Smith had really been a legendary figure called ‘Dog’ Smith who had wandered the streets of Surrey disguised as a beggar with a dog, allocating money in his will to the villages that gave his dog a bone.

The reality, that Smith was a moneylender who wanted to exert precise control over his legacy and ensure those who owed him money did not escape repayment, was a less attractive tale to the Victorian population of London.

Curtain Road, Shoreditch, 2018

Criticism of his payday loans business results in the modern Henry Smith making a public apology.

“I wholly regret my decision but learned due diligence and to check more studiously in future,” he says in an interview, insisting he never had any day-to-day involvement in the company.

A year after his payday loans company collapsed, failing to make the final payments ordered by the Financial Conduct Authority, Smith uses the interview to announce he is setting up a charity called The Wickers to help young Londoners who might be tempted by a life of crime.

“The Wickers Charity is showing them that there’s another way, the proper way to earn money,” explains Smith in a press interview.

The Wickers receives positive coverage from MailOnline, the outlet that previously led criticism of his family’s payday loans business. Sadiq Khan, the mayor of London, visits one of its projects. Smith talks about moving his family back from “soulless” Knightsbridge to the East End where he grew up in order to reconnect with his roots.

Smith then throws himself into conducting elaborate sponsored fundraising efforts, raising £150,000 after trekking to a mountain in Antarctica and almost losing his nose in the process. His charity continues to work with young people in east London, helping young people in east London during school holidays. In 2024 it spent £200,000 of its £670,000 income on fundraising activities, which include a glitzy white collar Great Gatsby-themed boxing gala.

Silver Street, 1627

When the 17th-century Henry Smith was drawing up his will he specified a bequest to help the victims of Barbary pirates. At the time a major public concern was Muslim pirates capturing Christian British sailors, taking them to North Africa, and forcing them to convert to Islam, later inspiring a key plot element in Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe.

The context of the era was very different to today but fear of the distant foreigner was a cause that could be used to stir public passions and raise money. Smith set aside a thousand pounds in his will to pay the ransoms of “the poore captives being slaves under the Turkish pirates”.

Centuries later, the 21st-century trustees of his charity will reinterpret this clause supporting the victims of piracy through helping victims of modern slavery and sex trafficking. The money left by the Tudor money lender will grow into a large pot that is used to offer assistance to refugees and people who have been victims of domestic abuse.

London, 2024

Brogan Garrit-Smith, the modern day Smith’s daughter and a former director of his payday loan company, has reinvented herself as a podcaster interviewing the likes of porn star Bonnie Blue, conspiracist David Icke, and former GB News presenter Dan Wootton.

One episode of her podcast is a two-hour interview with far-right anti-Islam campaigner Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, also known as Tommy Robinson. Garrit-Smith says that she has debated whether to invite him on the show but ultimately concluded “this podcast is about speaking to people wherever they are heading”.

During the episode Robinson repeated false remarks made about a young Syrian refugee which breached an injunction on him talking about the case. Robinson’s remarks on Garrit-Smith’s podcast will later be cited by a high court judge as one of the reasons Robinson has to be jailed for contempt of court.

Pentonville Road, London, 2016

Almost 400 years after the death of its founder, the Henry Smith Charity has expanded its remit to deal with social injustice across Britain. But the requirement to help needy “kindred” of its founder remained. In the 2010s, to ensure it was reaching everyone it needed to, the charity embarked on a massive genealogy project to track down the descendants of Henry’s sister.

More than 4,500 people were identified as having a family link. They live around the world although some of them are still based in areas of London that would have been known to the Elizabethan Henry Smith. To make a claim the British-based descendants had to show genuine financial need. This could be living in poverty, or a temporary fix like an expensive appliance, such as a washing machine, breaking. Kindred going off to university can receive a grant equivalent to 40% of a maintenance loan.

Many of the people who were contacted by the charity believed the offer was too good to be true, or a variant on the classic ‘Nigerian prince’ online scam. The truth, that they were the lost descendants of a 17th-century moneylender and therefore potentially entitled to a small share of his still-existing fortune, was hard for them to fathom.

Deptford, 2025

Lewisham councillor Will Cooper, the cabinet member for housing, is running surgeries out of Vive Living’s property while helping the tenants fight the evictions ordered by the modern Henry Smith’s company.

With the involvement of local MP Vicky Foxcroft and renters’ rights groups it soon becomes apparent that many of the properties let out by Smith’s company had been unlicensed.

In some cases, according to both Cooper and a lawyer involved in the cases, this made the no-fault eviction notices invalid. In other cases tenant deposits hadn’t been protected in the proper manner. Some homes were occupied by more than two unrelated tenants but they hadn’t been registered as Houses of Multiple Occupation (HMOs) by Smith’s company, meaning the tenants could apply to have their rent paid back.

“They were treated appallingly by the landlord and the landlord didn’t have the correct licenses in place,” says Cooper. “Some of them got significant payouts to leave.”

The tenants still lost their homes. But they didn’t go down without giving Smith’s Aitch Group a bloody nose — often receiving thousands of pounds in compensation, or simply payments to settle their claims and move out. Some simply stayed put even as the builders moved in and refused to leave until they were paid to go. Other cases are ongoing.

“You can get up to a year’s worth of rent back over the unlicensed period,” says Cooper. “For some households that will be on top of money they were paid to leave. You have to have respect for tenants and respect for people. If you are trying to do this, you should at least do it by the law. If you’re going to be a landlord you have to look after tenants and treat them with respect.”

Wandsworth, December 2025

When the earlier Henry Smith was growing up in Wandsworth it was a small village in Surrey known for using the fast-flowing River Wandle to power mills. Now it is very much part of London.

Just before Christmas London Centric visited All Saints church, where Smith is buried and where his memorial, his only known likeness, survives on a wall.

There’s almost nothing the 17th-century moneylender would recognise in the surrounding area. Opposite the church, rebuilt after Smith’s death, are a pilates studio and a row of Victorian buildings housing vape shops and hairdressers by a busy road. A large residential tower is being built nearby as part of the ‘Wandsworth Mills’ development, with the area’s former industry turned into a marketing line. The only constant is the Wandle, that now winds its way under the nearby shopping centre.

Smith finished his life as a fantastically rich housebound miserly man. It was in death that his real legacy was formed. His stubborn insistence on setting out the precise terms of his will, combined with his trustees’ investment in a farm that would later become the site of some of the world’s most expensive property, means the charity operates in ways that its founder would never have imagined.

Henry Smith’s Charity eventually sold the land around South Kensington in the 1990s and diversified into a brand new range of investments. It now has an enormous endowment of almost £1.5 billion. Last year it renamed itself as the Henry Smith Foundation and describes its mission as existing to tackle poverty and create “a more just society”, distributing £61 million to causes across London and the UK that can “create social change now”.

Yet the requirement to help the thousands of descendants of Henry’s sister remains as a small part of its work. In 2024, the charity awarded 472 grants worth £1.1 million to 223 “poor kindred” who needed assistance.

Deptford, 2025

Just before Christmas London Centric revisited Deptford to double check the facts in this story. The former tenants of the modern Henry Smith’s Vive Living property said they feared they were the victims of an attempt to get ahead of the government’s forthcoming Renters Reform Bill, which will soon make no-fault evictions much harder.

We found the building, freed of its long-term tenants, was now occupied by a student housing company called YourTribe, which is part-owned by Henry Smith. Yet we could not find any planning permission for change of use to student housing.

When we raised the matter with Lewisham council they said they are investigating its use as “unauthorised student housing”.

The modern day Henry Smith’s PR representatives said they would not respond to any of the matters in this article, including questions about how he felt about his wealth and role in London society.

When London Centric asked whether the eviction of longstanding tenants in Deptford, many of them on tenancies that did not meet legal standards, had been carried out to enable the reuse of the building as unlicensed student accommodation, we did not receive a reply.

Maryam, the former resident of the building, said there had been a positive side to the evictions. She realised how fellow residents could help each other and local politicians made a tangible difference: “People came together. That was amazing. Vicky [Foxcroft], the MP for Lewisham, was amazing. The WhatsApp group is still active.”

Still, the experience of her treatment as a private renter at the hands of Smith’s Aitch Group left a bad taste: “Everything just happened so quickly. I just felt like they were bastards, to be honest. They don’t care, they just look at numbers. We were just payments coming to their bank accounts.”

London, 2026

London fortunes rise and fall, shaping both the individuals and the city itself. A lot has changed in the last 400 years but the capital’s property and loan markets still have the power to transform the lives of those bold enough to take part in them.

How the city’s richest figures are remembered is often a matter of luck, defined by whoever is writing the history of that era.

Ultimately, it’s a quirk in the annals of London’s history that these two men share a name. Neither would entirely recognise the other’s city. But this story of two Henry Smiths, past and present, is a reminder that while so much changes about London, some factors remain constant.

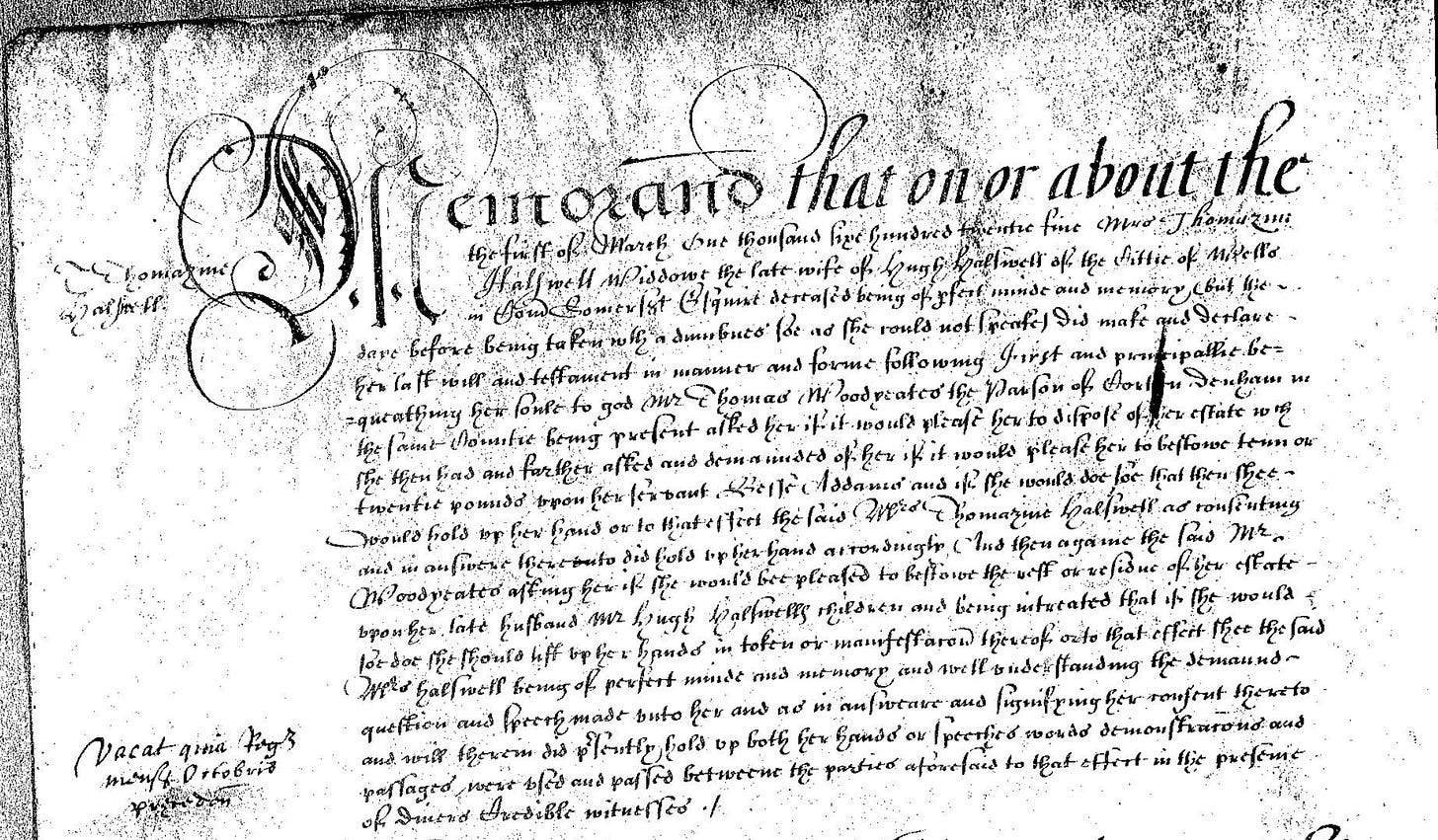

Henry Smith’s original handwritten will from 1628 can be read here, accessed via the National Archives.

For further reading on the little-known historic Londoner, Lucy Lethbridge and Tim Wales’ biography, which was invaluable in writing this piece, can be bought here.

Want to get in touch with London Centric? Send a WhatsApp or an email. Please do forward this article to anyone who might find it interesting.

Normal service will be resumed next week, with lots of original news stories about modern London.

For now, we’d like to thank both Vittles and The Fence (who are running a crowdfunder with excellent prizes) for mentioning London Centric pieces in their round-ups of the best journalism of last year.

I’m one of the kindred of the Henry Smith Foundation. In the 1940s, it helped my father with a grant to go to university which undoubtedly made a huge difference to his life. One of the amazing things is that they have the whole family tree right back to Henry Smith’s sister which is a lovely thing to have.

Fascinating article. We need more writing like yours. London has so many unknown stories.