Your upmarket Deliveroo might be made by your local kebab shop

"On one hand, it’s a lifeline... But on the other hand, it’s a harbinger of doom.”

Welcome to London Centric, where you can scroll down for a fascinating story revealing the next big trend in London food delivery, which is upending the economics of small neighbourhood restaurants and takeaways.

But first, some updates on previous stories:

Two of the tacky gift shops featured in our investigation into brazen tax evasion in the centre of London will soon close down – to be replaced by a new giant 24 hour casino that was just approved by Westminster council. The site is owned by Asif Aziz, the billionaire landlord (and regular character in London Centric) who owns the Trocadero building near Piccadilly Circus. We’re sure that Aziz’s Criterion Capital and casino operator Genting will be doing their best to ensure that the gift shops currently occupying the site pay all their taxes before they vacate the premises.

Who says local journalism doesn’t get results? The same day that we highlighted that the mysterious Tesco ramraider of east London had failed to pick up their vehicle, someone came along to finally remove it. We’d like to think the driver is a reader but fear it’s more likely to be someone in the local council.

Our report on the troublesome relocation of the restaurants at Elephant and Castle (as mentioned in Vittles) prompted an interesting debate in the comments about how some restaurants in the area have survived. Zoë Garbett, the Green London Assembly member, told Sadiq Khan at mayor’s question time she “wanted to ring the alarm bell” about the situation in Elephant and Castle and other small local markets. Khan replied, “I’m aware of the regeneration of Elephant and Castle and the impact on the market, and the transitional arrangements. I wasn’t aware of the individual cases but I’m more than happy to look into those.”

Times columnist Matthew Syed has been in touch following speculation at the Conservatives’ annual conference that he might be interested in being the party’s candidate to run City Hall. The new member of the Tories said that after “a crazy few days” at party conference he “won’t be standing for mayor”.

Remember our report on the curious legal status of those blue-jacketed fundraisers outside stations, who give the impression of being charities but aren’t? Inside Success, the pioneers in this space, have filed their latest accounts. The organisation’s latest accounts said financial performance was “satisfactory” but warned of future tough trading due to “increased competition”, presumably referring to the ever-growing number of copycat groups also wearing blue jackets and standing outside stations.

Thank you to all the paying supporters who make London Centric possible.

If you want to get in touch, please send an email or a WhatsApp.

Why your local London kebab shop might be cooking your next upmarket Deliveroo

By Riya Sharma

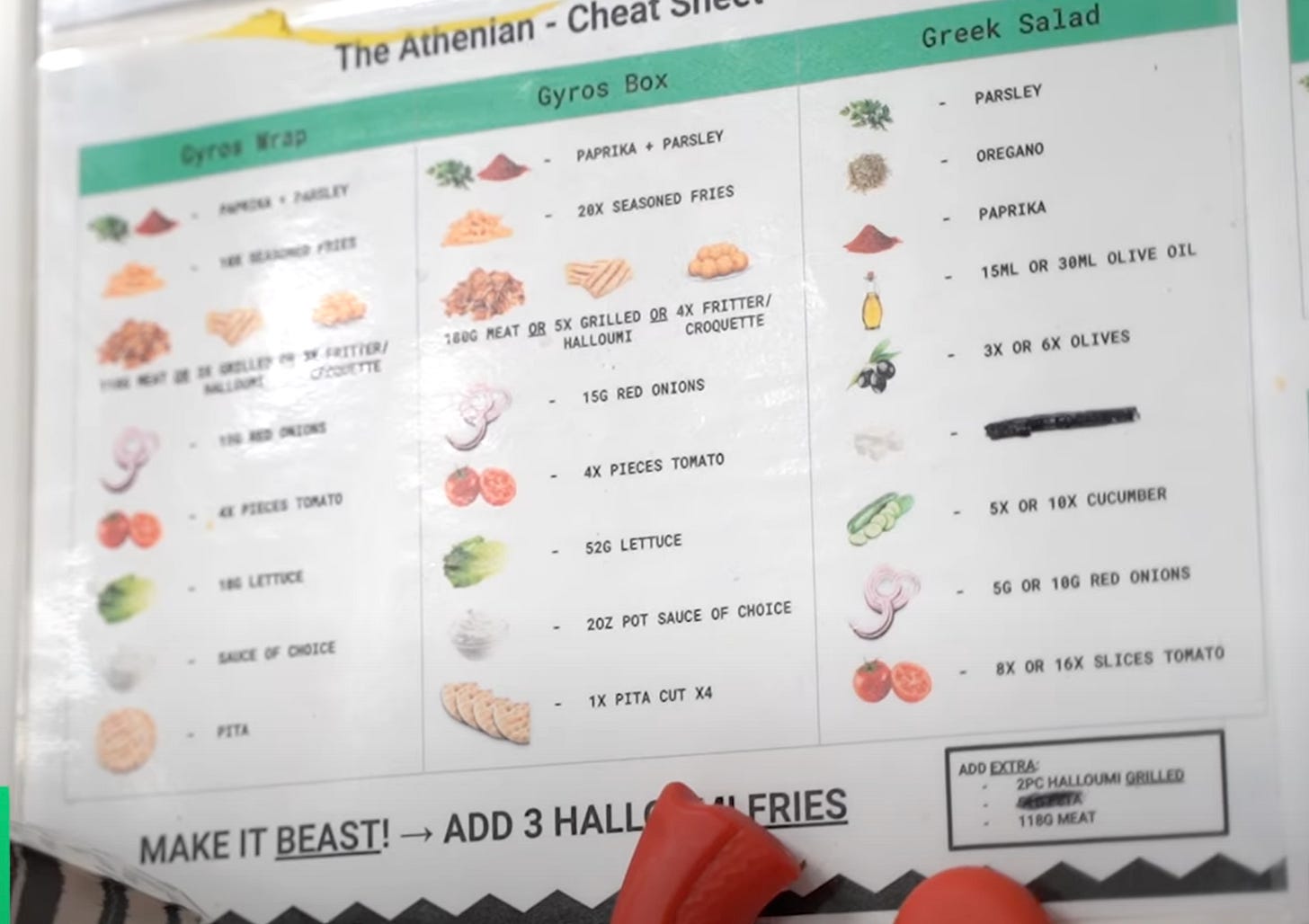

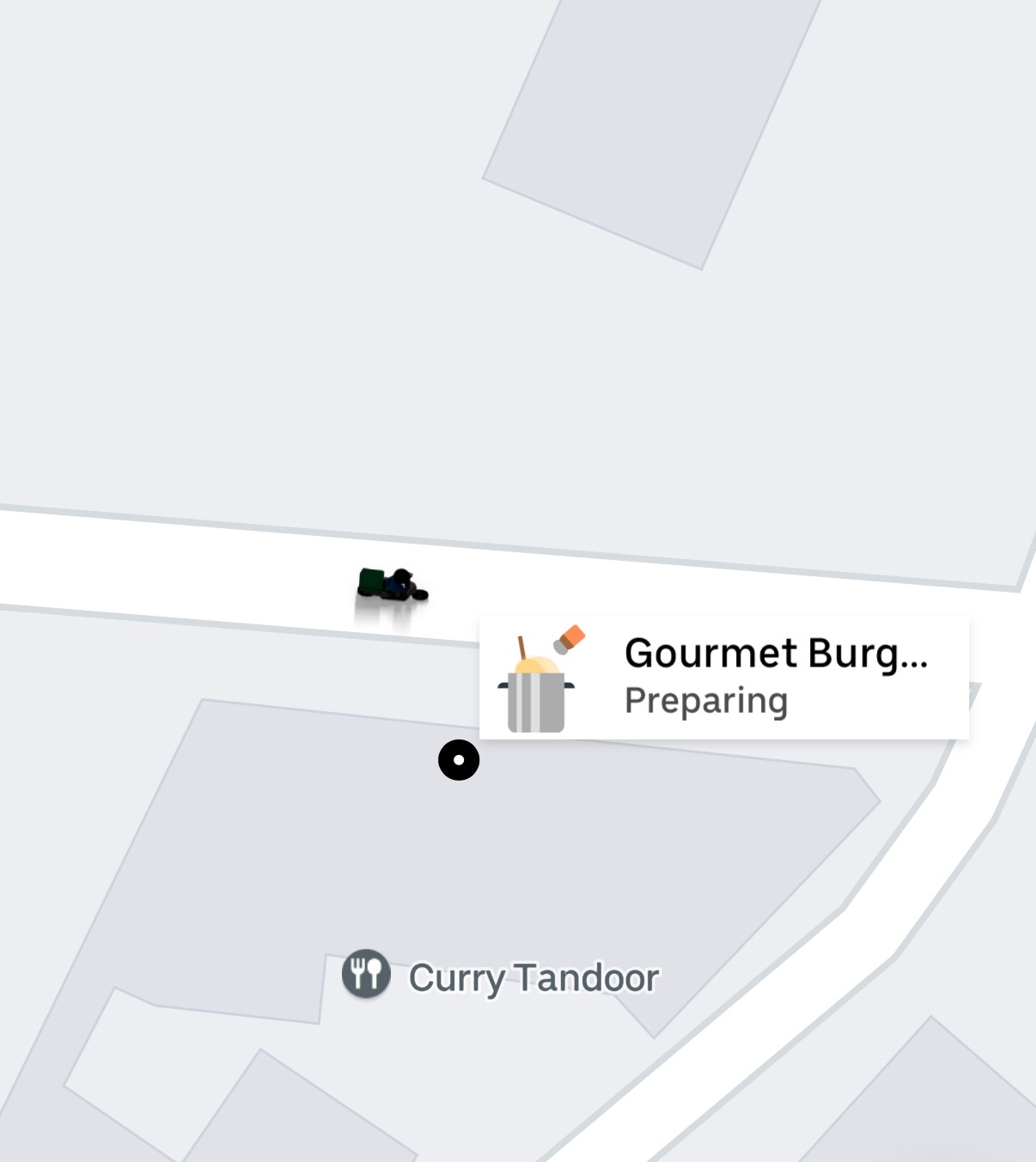

At the end of a busy high street in Beckenham, south London, a Greek restaurant called The Athenian (slogan: “Like Athens but here”) serves a traditional mix of halloumi, pork wraps and gyro boxes. But in the back of the premises a chef moves between preparing the restaurant’s own dishes and cooking orders on behalf of Gourmet Burger Kitchen (GBK), grabbing packs of beef patties and fries to fulfil delivery requests. Deliveroo and Uber Eats drivers come and go at a steady pace, picking up GBK “handcrafted burgers” in “artisan buns” that have never been near a GBK employee.

Meanwhile, on the Isle of Dogs, a mile from the towers of Canary Wharf, an unassuming local takeaway called The Little Kebab House is doing a similar trade. Walk in and you’re able to order grilled halloumi or a lamb doner. Yet outside is a steady stream of Deliveroo drivers picking up fried chicken burgers carrying the name of Coqfighter, a buzzy “Instagram sensation” restaurant with branches in Soho, Kings Cross, and Finsbury Park.

Again, what the hungry finance workers of Canary Wharf don’t realise when they order an £11.50 Nashville Hot fried chicken sandwich from Coqfighter is that it has been cooked inside a neighbourhood kebab shop.

Welcome to the world of ‘host kitchens’, the next big thing in London’s food delivery scene, as cash-strapped neighbourhood restaurants and takeaways run side-hustles secretly cooking delivery food on behalf of more established brands.

London Centric compared the pick-up addresses of dozens of major brands on UberEats with the real-life takeaways and restaurants located there. We found Chinese restaurants churning out American barbecue, fried chicken coming from kebab shops and Mexican meals from pizza outlets. Brands such as Tortilla and Beer + Burger are getting in on the action and signing deals to outsource their delivery in this way.

If everything goes to plan, happy customers will never know or care about the true origin of their delivery, which is cooked according to instructions from the parent brand. Every London suburb will gain access to their favourite food from the established central London brand of their choosing. And a cut of the money from each order will go to the local restaurant just around the corner that actually cooked the meal.

But it raises questions about the future of the capital’s food scene, whether customers would be happy if they knew where their meal was coming from and what it means for the future of the neighbourhood London restaurant if this becomes more profitable than providing a place to sit in. With customers shying away from casual dining due to what the writer Harry Wallop dubbed “bill shock”, where a quick meal for a family of four can easily cost over £100, this might be the only way to survive.

“On one hand, it’s a lifeline,” said food writer Andy Lynes. “But on the other hand, it’s a harbinger of doom.”

“People don’t actually mind where it comes from”

Over the past decade, Londoners have grown used to the idea of ‘dark kitchens’, where warehouses and sheds in car parks are turned into fast food delivery factories for established brands such as Dishoom, Five Guys, and Rosa’s Thai. What’s exploded this past year is the shift to ‘host kitchens’, where bricks-and-mortar restaurants ask their chefs to cook for different brands for the delivery market while continuing to prepare their own in-house cuisine.

The reason for the shift is simple. Dark kitchen sites are unpopular with their neighbours, hard to staff with chefs willing to work in them, and difficult to run at a profit. Rather than find someone willing to take on the up-front cost of building a new dark kitchen, the thinking goes, why not simply use existing kitchens already installed in neighbourhood restaurants?

The main driver of this trend is Growth Kitchen, a London-based matchmaker pairing under-utilised cooking space with restaurant brands who want to be available across the whole capital on Deliveroo — but don’t want to take on the cost of opening new branches.

“If it arrives hot and it’s all the same, using the same ingredients, people don’t actually mind where it comes from,” said Growth Kitchen’s marketing manager Chris Lam.

Local restaurants apply to Growth Kitchen and if they meet food safety and partnership standards, they’re paired with one or more delivery brands. The local restaurant’s chefs are then given a couple of days of training to learn how to prepare each brand’s dishes, along with detailed step-by-step laminated instructions to pin up in the food preparation area. The host kitchens cover the costs of equipment, ingredients and packaging, while paying a cut of sales to the parent brand. According to Growth Kitchen, typical revenues range from £2,500 to £8,000 a month.

The company pitches its model as a lifeline for London restaurants squeezed by rising energy and staffing costs. Pubs, in particular, are keen.

“They’ve often got quite nice kitchens and a lot of space,” Lam said. “They might be busy when it’s a good weather day, but when it rains, the footfall going into the pub to drink is probably down and delivery in their local area might be up,” he said. “It’s a way to balance out the use of their kitchen space.”

Growth Kitchen used to run dark kitchens but ditched them 18 months ago, with the model considered to be unprofitable without enormous volumes of food being produced. Now, it works with around 150 host kitchens.

The company sells the idea of ‘restaurants as a service’, playing on the Silicon Valley tech idea of ‘software as a service’, where extra cloud computing capacity can be obtained or discarded according to need — except in these cases the capacity is real-life chefs and real-life local restaurants. The big restaurant business turns up with the recognisable brand, the recipes, and a basic training guide. The local kitchen provides the labour and the capital investment in the site.

“By day, it was a Chinese restaurant, in the evening they were doing American barbecue”

It sounds tidy enough on an investor pitch deck. In real kitchens, it’s a little less neat.

Some brands impose restrictions to protect their recipes. For instance, a fried chicken delivery brand will often decline to use another fried chicken restaurant as a host kitchen, said Lam.

Early attempts to pilot the host kitchen model started to take hold during the pandemic. A former general manager of an American barbecue brand spoke to London Centric. Her job was to train partner restaurants on the brand’s recipes and processes, sending over detailed specification sheets along with ingredients.

Her brand partnered with a Chinese restaurant in Fulham.

“By day, it was a Chinese restaurant, in the evening they were doing American barbecue,” she said. Her team supplied everything from bread to tomatoes — sometimes even fryers — and seasoning blends for the chips. Some kitchens fared better than the others; their partnerships lasted about three months.

The model is risky though, she said, as established brands cede control over the production of their food to the chefs in the host kitchens. Poor reviews can push a brand down delivery app rankings, making the effort “more trouble than it’s worth if you’re a small business.”

“You don’t know who’s handling your food,” she said. Bigger brands might be able to afford the risk, but smaller ones can’t.

That uncertainty might also reveal a cultural challenge. Unlike dark kitchens, which are purpose-built for delivery, food writer Lynes says that host kitchens operating inside functioning restaurants can sting for chefs and owners. It’s a “bit of a hit on people’s egos” to cook someone else’s food if your existing offer isn’t making enough money, he said, adding that it’s “probably something you do not want to publicise.”

For dine-in customers, the constant flow of delivery drivers can be disruptive and change their relationship with that restaurant, he said. The restaurants are “cutting off their own legs” because they “want people to come out, but they’re enabling people to stay at home,” he said.

“Most people never check where their food comes from”

Utku, who declined to give his second name, has run The Little Kebab House in Canary Wharf for 15 years after inheriting it from his aunt. He owns several other restaurants across London.

In 2021, he experimented with running dark kitchens in Battersea and near City Airport. The kitchens were large warehouse-style facilities rented out to delivery-only brands. Within six months, he pulled out. Rents had spiked, he said, wiping out profits. “It’s really hard to work in a dark kitchen. It’s not really popular anymore; people really complain about the prices.” He also described neighbours’ complaints about late-night noise and smell, which made councils reluctant to approve new dark kitchen permits.

Walk into The Little Kebab House today and the front counter still serves kebab plates, burgers and meze. But in a separate kitchen at the back, out of sight from walk-in diners, a single chef works shifts dedicated solely to orders for The Athenian and Coqfighter. (The trade goes in multiple directions at once; while the bricks-and-mortar Athenian outlet in Beckenham is doing GBK, it has simultaneously outsourced its own brand to different host kitchens.)

Unlike some other host kitchens, Utku insists that he keeps the two operations distinct: separate equipment, materials, different fridges and freezers and strict protocols on cross-contamination. He estimates that, between Athenian and Coqfighter deliveries, he handles an extra 100 orders each week. The additional revenue allowed Utku to hire another employee.

Other nearby restaurants close to Canary Wharf are adopting similar strategies, he said: an Indian restaurant down the street makes burgers for the delivery market and a local Asian restaurant cooks pizza and fried chicken to be despatched into insulated rucksacks on the backs of cycle couriers.

Opening his UberEats app, he is able to find 813 food delivery options in the area, enormously up on the last time he checked and far outpacing the number of ‘real’ restaurants. He scrolled through the menus, pointing out which well-known brand names offer delivery with their food cooked at local restaurants.

“Most people never check where their food comes from,” he says.

All of this represents a shift to a more homogeneous version of food delivery, where the money flows to recognisable brands that can afford marketing and work algorithms. Rather than using trial-and-error to learn which of your local takeaways cooks the best burger, customers want a standardised brand that they can order from anywhere in the capital.

Having a unique tasting recipe, said Utku, increasingly matters less than having a logo customers immediately clock when they’re scrolling through delivery apps.

He said he knows of five different burger brands selling essentially the same recipe under different names: “One calls it a Truffle Cheeseburger and another calls it Truffle Rascal,” he said.

“People are eating earlier, they’re going out less, they’re eating in restaurants less”

If you suddenly notice GBK being available on food delivery apps in your corner of London, it might be the indication of a new trend — the rise of the “zombie restaurant brand” that people are familiar with but no longer actually visit. After a rapid private equity-backed expansion during the 2010s GBK has closed many of its restaurants and recently sold a dozen of its remaining sites to rival Honest Burger.

According to messages seen by London Centric, GBK is now using Growth Kitchen to seek local restaurants across the capital to cook their burgers in locations stretching from Croydon to Belsize Park, and Shepherds Bush to Bexleyheath. The entry requirement is a four-star food hygiene rating. When hungry people are mindlessly scrolling through Deliveroo, the GBK logo might be enough to make them stop and order – even if the food production is outsourced.

London food writer Marshall Manson says it’s time to be understanding of the challenges of running a restaurant and sees the trend towards host kitchens as a pragmatic response.

“They’re under more cost pressure than they’ve ever been,” he said. “People are eating earlier, they’re going out less, they’re eating in restaurants less.”

Because people aren’t going out to eat at 9pm, restaurants are losing their second seating times, making it harder for operators to turn a profit. “Everything is costing more,” he added, pointing to rising overheads including national insurance.

London restaurants have always responded to market conditions and juggled cuisines when it made financial sense, resulting in ‘Chinese chippies’ and other hybrid takeaways.

For Manson, the host kitchen model offers a way for local restaurants to survive and protect themselves. “Who cares that it’s not on the front door?” he said.

Down in Beckenham, it was time to test the product.

Half a mile from the Athenian we ordered a Classic Veggie burger. The staff at the Greek restaurant momentarily stopped making gyros and cooked the burger, which was put into an unbranded box and sent out to us with a local delivery rider. It was fine. The flavours were uninteresting but it struck a reasonable balance between being soft and crisp. It had a respectable crunch. All of this cost £14.66 — which had to be split between Deliveroo, the delivery driver, GBK, Growth Kitchen, and ultimately the local restaurant that had to cook it. It is simultaneously not cheap, while also not making much money for the people actually making the food.

Ultimately, though, becoming host kitchens might be the only option that some of London’s smaller restaurants have left.

“The way people approach dining has evolved since Covid,” said Manson. “Ordering for home is a more important part of our dining habits.”

If you want to get in touch, please send an email or a WhatsApp or leave a comment.

At risk of them getting wind of this hack and ruining it: you can filter out basically all the ghost kitchens by filtering for pick-up orders - tends to be only legit restaurants that allow actual customers to collect food themselves. You can then change it to delivery when ordering.

Jim - your writing is consistently interesting and insightful. I don’t live in London (I work there) but LondonCentric is by far the best local news site I know of. Also what starts in London ends up everywhere else soon enough.