Would your home have been under a motorway?

"The most astonishing and destructive thing never to happen to London," says the man who has spent twenty years researching the first true map of the unbuilt Ringways.

Imagine walking out of Camden Town tube station, turning north towards Camden Market and finding yourself facing a twelve-lane concrete motorway full of roaring traffic. This was the intended outcome of the 1960s Ringways plan to drive four giant circular roads through the capital in order to enable millions of Londoners to drive their private cars straight through the heart of the city.

I tend to focus London Centric on investigations into things that are happening now. But just occasionally it’s worth looking back and considering the route not taken by previous generations. I’m obsessed with how ideas that seem logical or necessary in one era can be viewed with bafflement just a few years later — and guessing which policies of our current era will soon be treated with the same disdain.

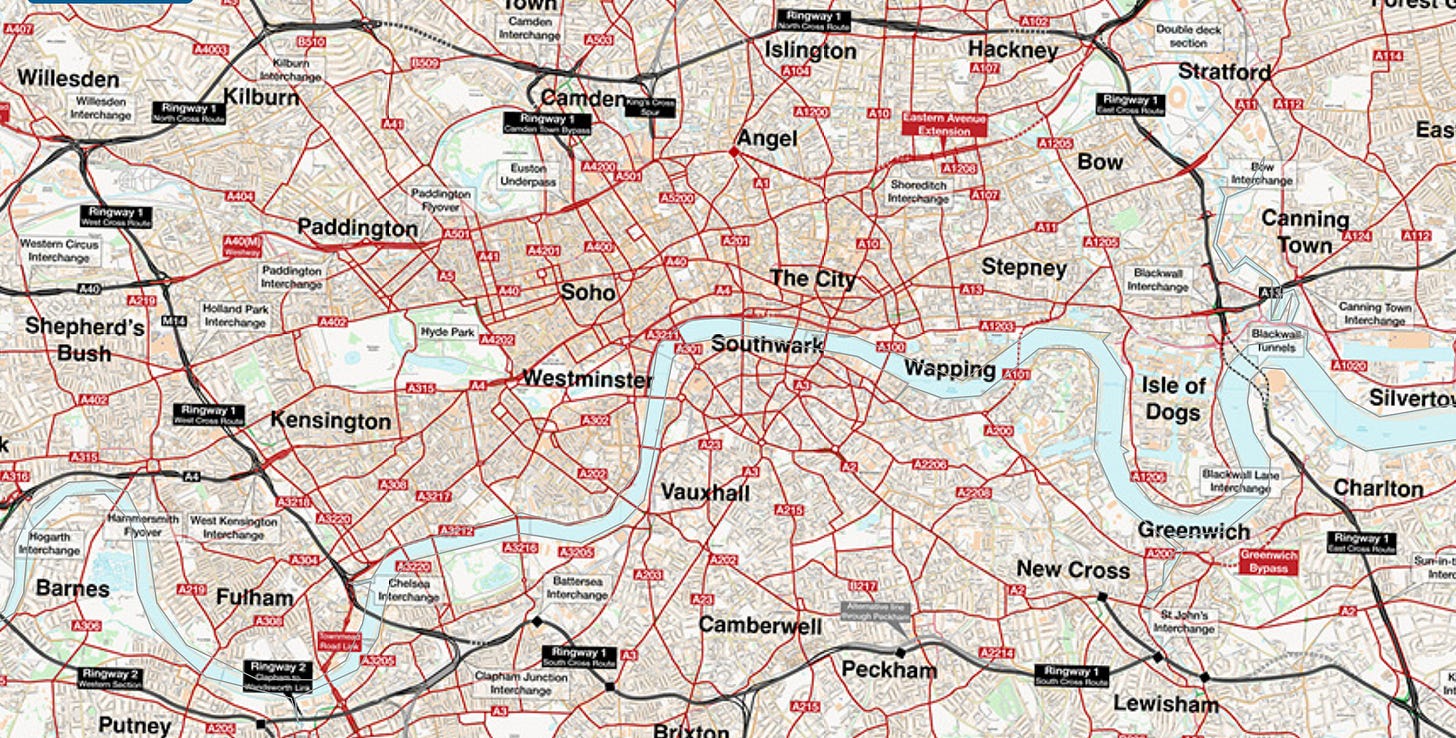

One person who’s even more fascinated with the Ringways than me is Chris Marshall, who describes it as “the most astonishing and destructive thing never to happen to London”. He’s spent two decades piecing together what he believes to be the first truly accurate map ever made of the abandoned plan to cover London with US-style motorways. This week he finally published it and has taken the time to talk it through with London Centric readers.

Scroll down to find out if your home would have been under a giant motorway junction — and see which parts of London would have disappeared for good under a road.

Got a story for London Centric? Get in touch with us here.

The man who spent 20 years building the first map of the London motorways that were never built

In the 1960s there was one big thing causing panic among the capital’s politicians and planners: the ever-growing popularity of the private motor car. London was being overwhelmed by booming car ownership and not enough was being done to avoid permanent gridlock. The proposed solution was the Ringways, hundreds of miles of orbital motorways that would cut through the capital, often elevated above the city.

Vast chunks of London’s Victorian housing and public parks would have to be obliterated to make room for these giant roads — but that was seen as just a necessary evil given the seemingly inexorable rise of the car.

The strangest thing, to our modern sensibility, was that there was cross-party political support and an academic consensus behind the plan — and even, initially, strong public support for road building as the solution to congestion.

“They all thought they were saving London, that there was a looming catastrophe and they could save the city,” says Chris Marshall, founder of the website roads.org.uk. “There was a lot of academic weight, political impetus, and a public sense that something had to be done about the traffic.”

The city would have to adapt to the car driver, rather than the other way around.

Marshall is an obsessive chronicler of British roads who has done more than anyone to keep the memory of the Ringways project alive.

“From the perspective of the modern observer, it has this sort of horror value,” he says, reflecting on the decades of work that has gone into building this map. “Twenty years in, I still look at the plans and think, ‘Oh my God, this is unreal’. The size of it never quite goes away.”

When Marshall says his is the “first ever map” of the Ringways, he means it. The Ringways were planned in the 1960s by lots of different teams, often working in isolation on individual aspects of the project with pen-and-paper designs. Marshall has pieced together the plans from original drawings found in archives. As a result no complete detailed map of the proposed London motorway network has ever been published before this week.

Even the people who spent decades of their life designing the network didn’t have access to what you’re looking at.

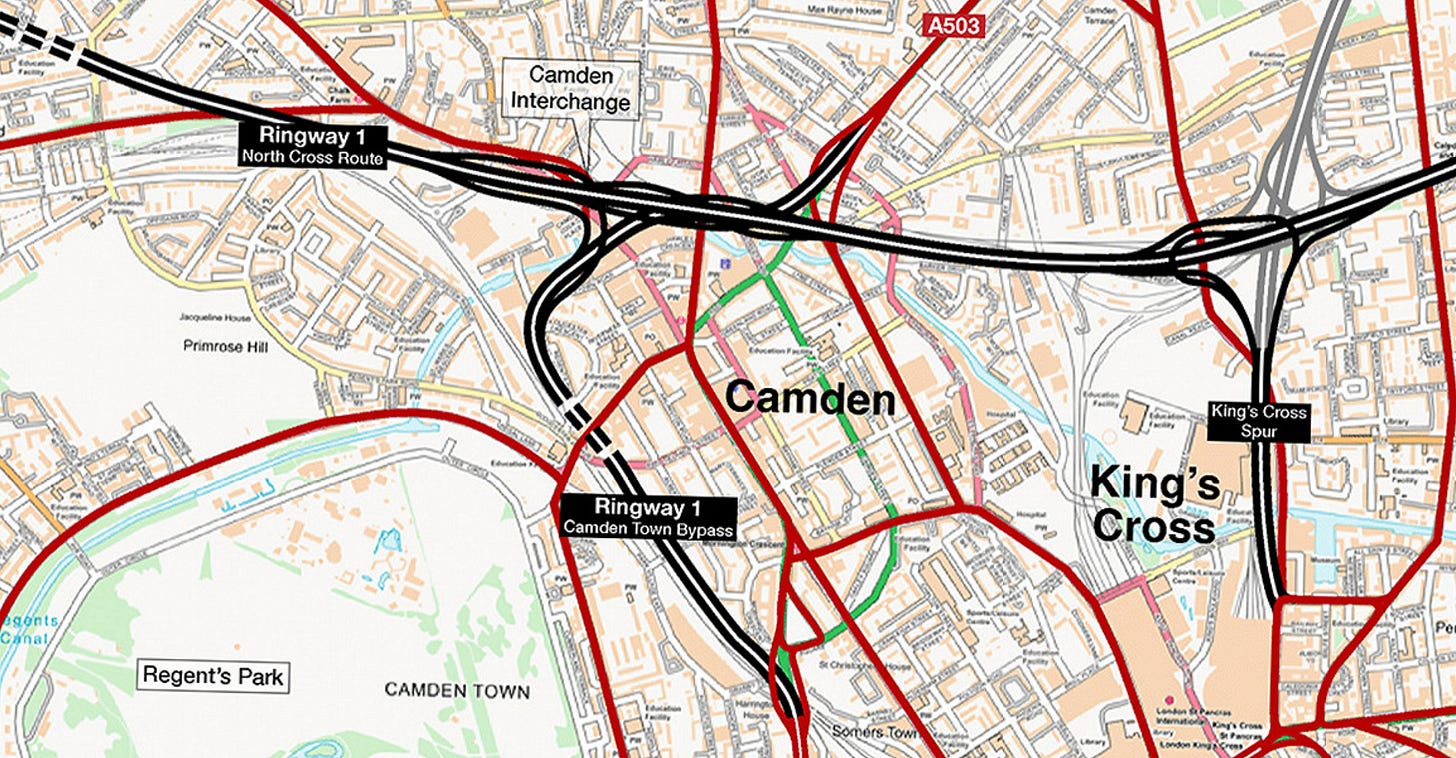

A giant motorway interchange would have replaced much of Camden

One of the most dramatic proposals was to stick a giant multi-level motorway interchange on top of Camden. The main through route would be twelve lanes wide (four lanes of traffic in each direction, plus two hard shoulders in each direction) as well as the inevitable sprawl of slip roads over the surrounding area.

The thinking was that this plan would save Camden by diverting car traffic around the main high street. The market area, now a hub for tourists from around the world seeking expensive street food and a photograph with a punk, was seen as a perfect site for a giant motorway junction.

“There was going to be a motorway passing through along one of the railway lines, plus this enormous three or four-level interchange with five arms reaching out in different directions,” explains Marshall. At the time London’s population was declining and many of the Victorian homes that now cost millions of pounds in gentrified areas were seen as life-expired slums in need of replacing with modern housing suitable for the 20th century.

“Everything you know and picture when you think about Camden would not be there,” says Marshall. “If you look at a map of the proposals and try to find the bits of Camden you recognise, they’re basically not there. All the things that make Camden what it is today would never have existed.”

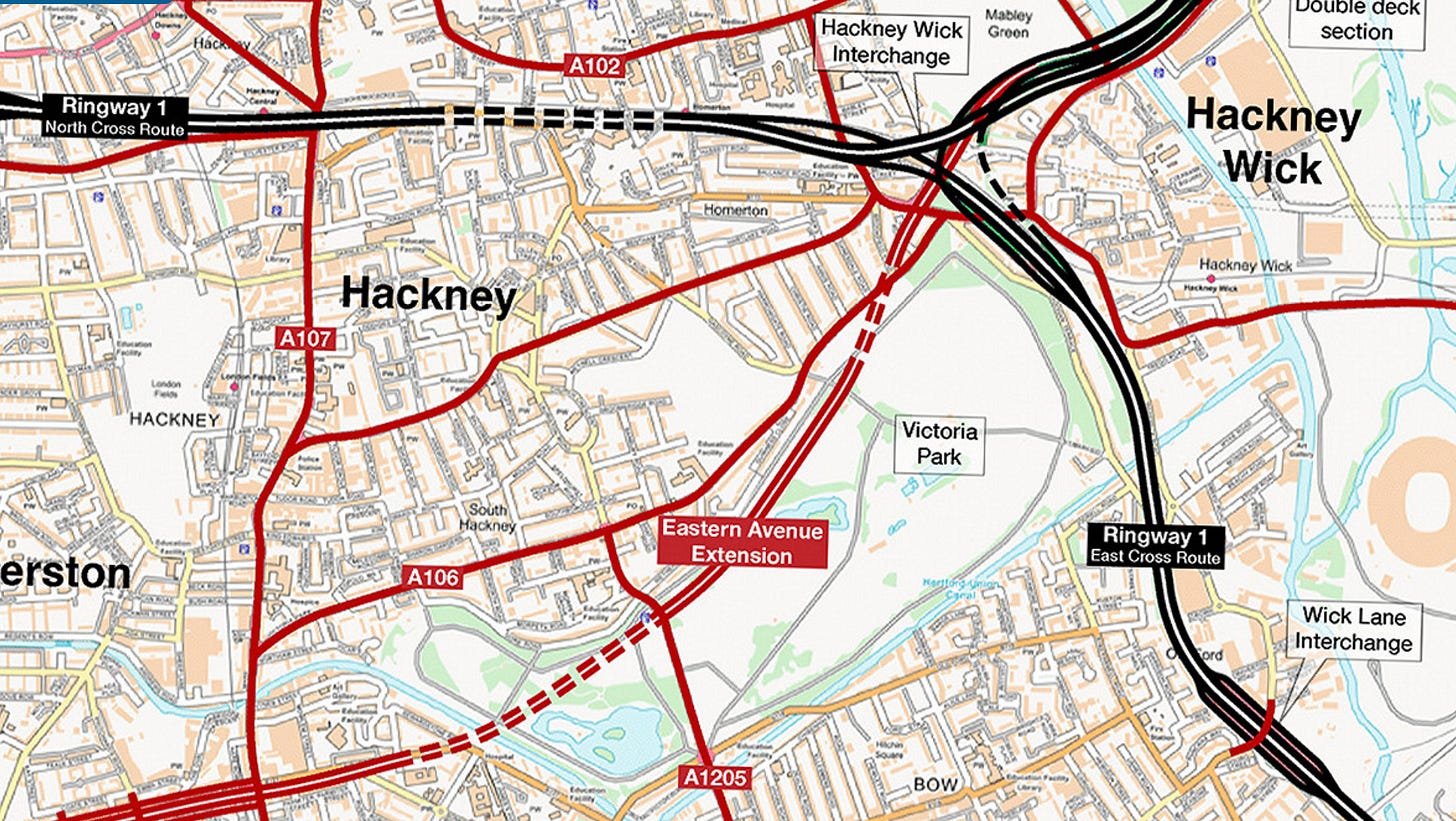

Victoria Park in east London would have been carved up by a giant feeder road.

Victoria Park would have had a major road running across its northern edge which would then carve a new route across Bethnal Green, dive into a tunnel along City Road, and then emerge at a new motorway junction at Angel in Islington.

“[Labour and the Conservatives] were trying to outdo each other in terms of investment and the scale of roads they’d build,” says Marshall, recounting how building big new roads was seen as a vote winner in the 1960s, as people who had just bought their first family car became infuriated by the experience of congestion.

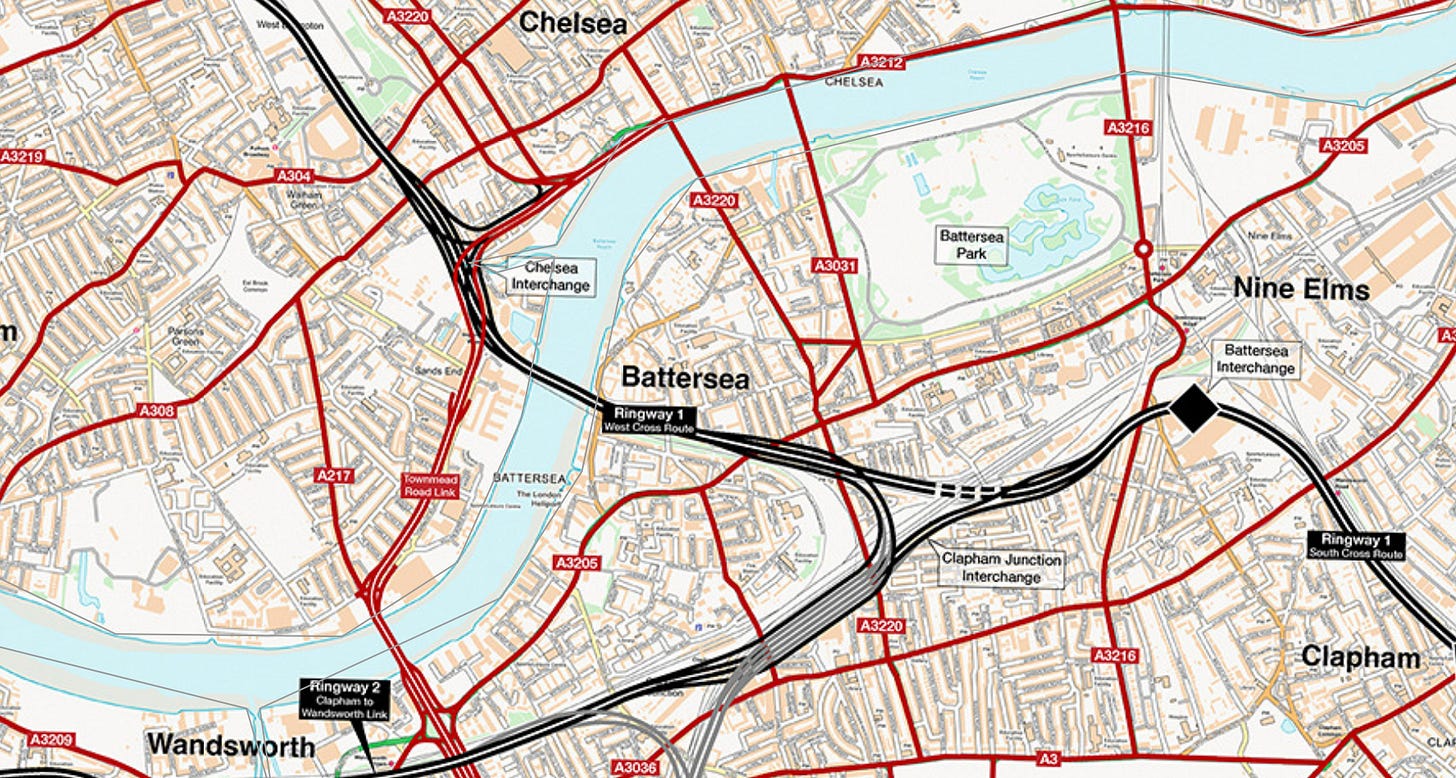

Chelsea would be full of motorway junctions with a giant interchange above Clapham Junction station

The main Los Angeles-style north-south inner London motorway would have been the West Cross Route, running down through Kensington, Earls Court, through Brompton Cemetery, then over the Thames to a giant interchange built on top of Clapham Junction railway station.

The road would have been at double height above the railway tracks, with interchanges at every level.

“The shadow it would cast on those low-lying lovely Chelsea terraces – you can’t even imagine how this would have changed the place,” says Marshall.

If you want to have an idea of its size then that’s easy — because some of the West Cross Route was built. If you’ve ever wondered why Westfield shopping centre in White City overlooks a giant sunken concrete motorway that disgorges traffic onto a series of small residential roads, this is why. The existing stretch of road was just a very short stretch of the planned route.

Goodbye Brixton, hello South London Expressway

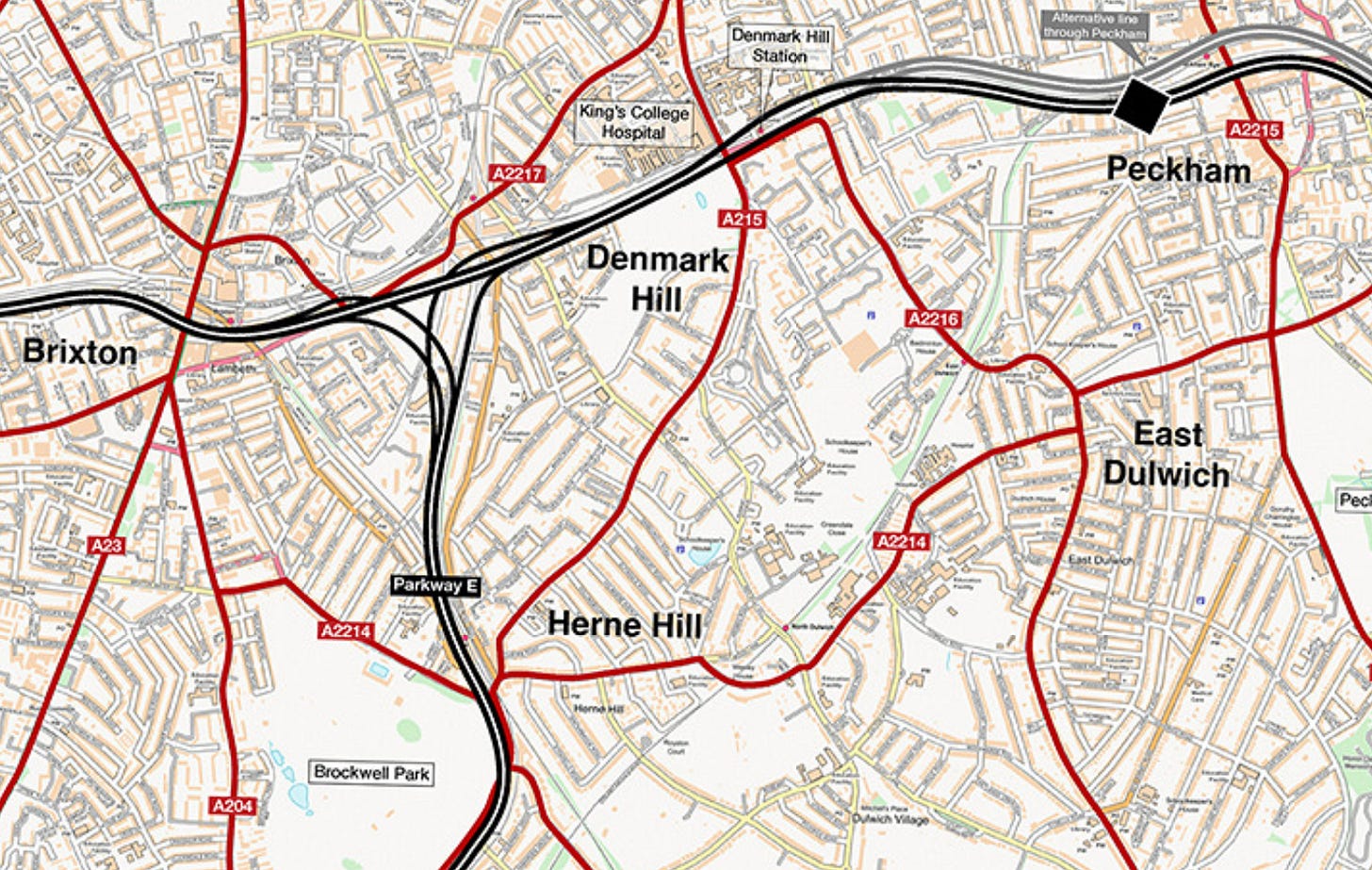

Anyone who has tried to drive across south London knows that it is quicker to wade through quicksand. The plan was to solve this with a giant motorway following the route of the railway now used by the London Overground’s Windrush line.

Peckham, Denmark Hill, and Brixton would have had their centres bisected by a giant concrete motorway — while the residents of Herne Hill would have had a giant parkway covering the cafes of Railton Road and winding its way around the edge of Brockwell Park. After demolishing much of Upper Norwood and Crystal Palace, it would link-up with Ringway 2, a motorway that would replace much of the area around Thornton Heath.

Perhaps the most infamous remnant of this plan is Southwyck House, a still-standing slab of social housing in Brixton that was built with the expectation that its residents would soon be facing an eight-lane motorway.

Kilburn would be overwhelmed by a giant road junction

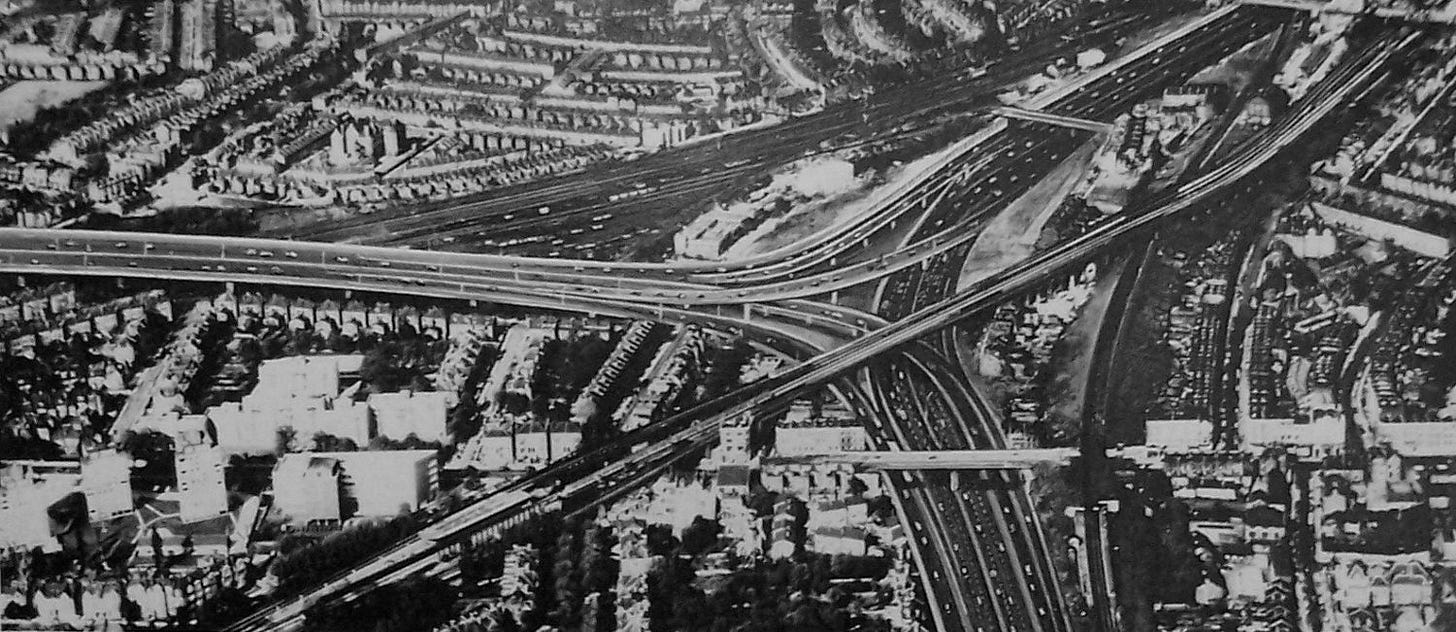

If this artist’s impression of the planned Kilburn interchange in north west London looks like a picture from US city, that’s because that’s where planners were taking their inspiration from. The designers looked at how American cities were responding to the growth of cars and proposed to copy their solution of blasting giant roads through suburbs and urban centres.

There was one problem, says Marshall: “What works in Detroit or Chicago really doesn’t work in a historic, densely packed British city like London.”

Eventually London realised it needed to adopt different techniques such as investing in public transport, bus lanes, and eventually congestion charging: “But before we got there, we tried importing this ready-made solution from overseas, and it got us the Ringways.”

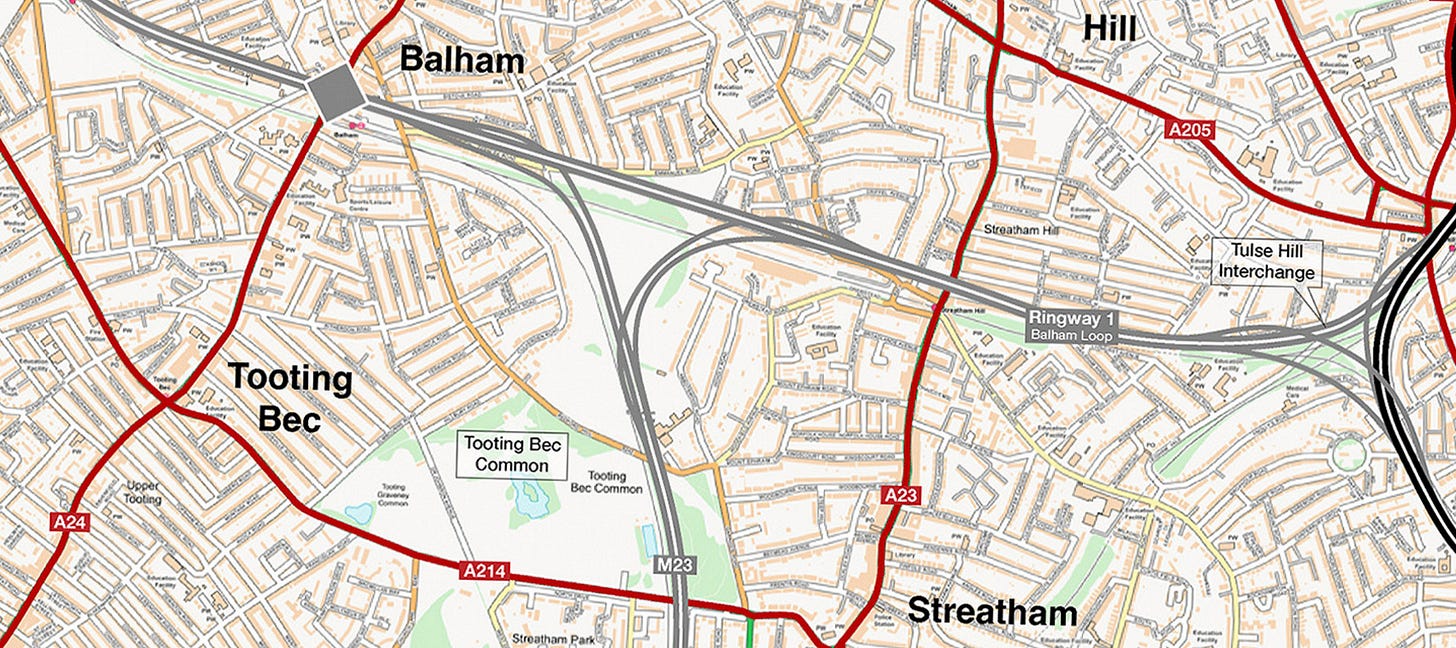

Tooting Common would have been turned into a motorway to Gatwick airport

The motorway engineers viewed London’s parks and open spaces as “handy open spaces to dump roads in”, according to Marshall.

A typical example was Tooting Bec Common in South London: “There were very few sensibilities about making things compact or reducing footprints in urban areas and they treated Tooting Common as this convenient open space to site slip roads.”

There are areas of the capital where this approach was taken and built. If you want a vision of the future that didn’t happen just go to Boston Manor Park near Osterley in west London, where the M4 heading out of London zooms past Sky’s TV studios and out towards Heathrow on a viaduct.

Suburban voters with cars who supported the principle of roadbuilding suddenly started to turn against the idea when they realised what it would do to their local open spaces.

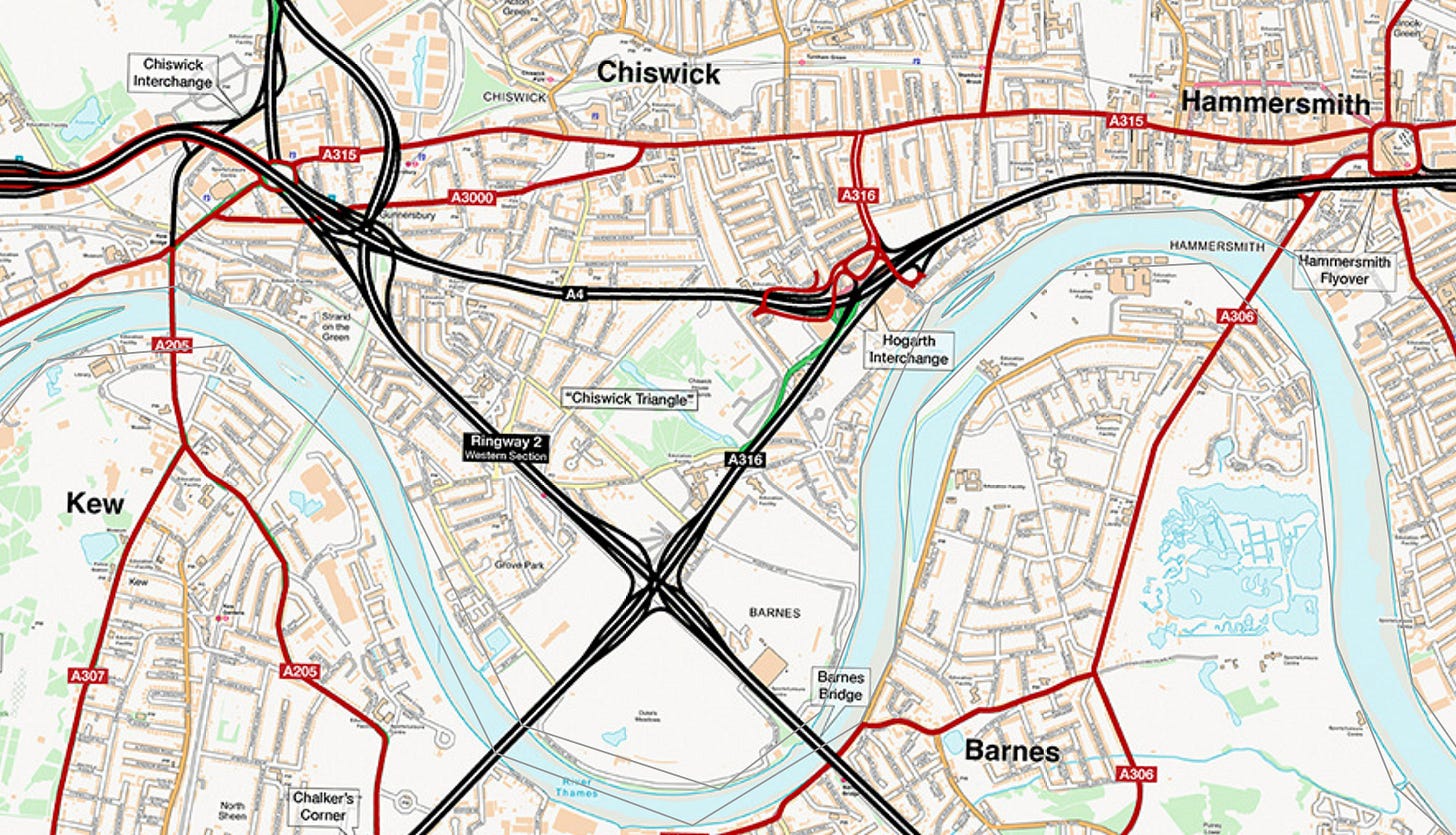

Chiswick would become a series of isolated patches of land separated by motorways

West London is one of the first areas where the plans were partially put into place — and the centre of later resistance to further expansion. The giant Westway motorway was built in the late 1960s ahead of the rest of the plan, flying through the air from Edgware Road out past Notting Hill — and looming over the streets around it.

“It’s not for nothing the Westway is this massive feature of music and culture that’s come out of West London ever since,” says Marshall. “It’s on people’s minds, it’s there, it’s inescapable.”

A little further south, the whole of Chiswick would have become a giant network of motorways. What’s now open playing fields near the Thames would be a series of expressways.

And some of the legacy of these plans is still there. If you’ve ever driven into central London from the south west, you might have crossed the Hogarth roundabout on a slightly rickety flyover. What you might not know is that this was built in the early 1970s as a temporary measure before the entire area was flattened and rebuilt part of the Ringways plan. When those plans were abandoned, the temporary structure was left in place — and it’s still there almost 60 years later.

The more you look around modern London, the more you see half-built visions of the capital’s 1960s road-based future.

The M11 in north east London currently starts at junction 4 in a strange landscape, where giant bridges criss-cross each other.

“The reason is they only built half the junction,” explains Marshall. “There were meant to be a whole lot of other motorways coming in and interchanging, slip roads and all sorts that would have made sense of what’s there now.”

When the plans were abandoned, the unused land was turned back into a public park and a recycling centre, he says: “It’s not a park where you’d ever sit and have a picnic — you’ve got traffic roaring past on both sides. So you now have this unhappy compromise: a park in north east London which is in the middle of a motorway and permanently smells like bins.”

The more you look at Marshall’s map, the more you can still see the echoes of the unbuilt plan in modern London.

The area around Trafalgar Square was due to be demolished to be turned into an efficient road system. When the 1960s St Vincent House was built behind the National Gallery, it was skewed to fit with the route of the planned road redesign.

On the southern edge of London, the motorway due to run from Gatwick into the city centre can be seen stopping mid-construction — instead disgorging drivers onto a single lane road through countryside villages.

And if you go out to Lewisham, land once intended for motorway construction was given to a community facility called the Ringway Centre.

So why didn’t the Ringways get built?

When the Greater London Council came into existence in 1965 the roadbuilding scheme was one of its flagship policies, a policy maintained under both Labour and Conservative leaders.

This attitude wasn’t unique to London, with every UK city planning how to cope with the car. Glasgow and Birmingham ripped up their city centres to build urban motorways. Leeds rebranded itself “Motorway city of the seventies” as a public statement it was embracing the future. Manchester still has the Mancunian Way across the edge of its city centre.

“It was the price they felt they had to pay,” says Marshall. “The motor car was coming. Something’s got to give. This traffic has to go somewhere, so we’d better make room for it. There have to be sacrifices.”

Instead, London politics intervened, especially when people started to see what these urban motorways looked like in reality. Many people rapidly concluded they didn’t really want giant new roads in their back yards, starting dozens of campaign groups against the development. A public inquiry slowed down the construction process.

At that time the capital was governed by the Greater London Council rather than a mayor, with the Conservatives in control of the city for much of the 1960s. When the 1973 local elections came around, Labour dropped its prior support for the Ringways and won the election by running an anti-roadbuilding campaign.

Not all construction stopped. The outer Ringway was finally built in the 1980s as the London Orbital Motorway, which before being rebranded as the M25 gave its name to a pioneering dance music act. As late as the 1990s there were giant anti-road protests in east London where squatters resisted construction workers pushing through a six-lane extension to the M11.

What does this mean for modern London?

Whether it’s the introduction of low-traffic neighbourhoods, the construction of the new Silvertown tunnel in east London, or the introduction of cycle lanes, debates over how London’s drivers get around the city are still as relevant as ever.

Marshall says he has pursued decades of research into the Ringways to keep the memory alive of the options we didn’t take: “One of the things that absolutely blows my mind about it is how the whole thing has basically been forgotten. If you go back to the 1960s, this was THE big political issue in London.”

The problem, like London Centric’s exclusive on Transport for London’s abandoned plan to charge drivers by the mile, is that people tend to not look at the options not taken: “There’s the old saying that history is written by the winners. The other thing about history is it tends to be a record of what happened.”

He says the legacy of the 1960s debate over the Ringways has become ingrained in the culture of London’s approach to transport, with new construction considered political unacceptable. This is why he’s dedicated so much of his life to documenting it: “This is all people talked about for about five years. And it just went away and people have forgotten about it. I don’t think we should forget about it. I think it’s important.”

With thanks to Chris Marshall for the archive photos and maps and sharing decades of work on this project.

You can lose hours of your day exploring his full map on the SABRE website and seeing how your home would have been affected, while his personal site that collates his incredible research on the Ringways plan can be found here.

One thing I adore about Chris’ work and self-maintained website is that it’s such a brilliantly personal and enthusiastically singular vision of what was good about the internet. There’s no clout chasing or viral strategy, he just wanted a thing to exist that spreads knowledge with a sense of humour and human writing. His work has ensured it has endured for two decades. I’ve been reading it for most of that time and borrowed heavily from it for my university dissertation on unbuilt roads and it’s just a joy to see something done for the hell of it.

Tremendous stuff on the Ringways. I’ve long had a bit about how cars don’t really work in London because so much of the city’s layout is millennia older than the infernal combustion engine, and this is also an interesting example of how that’s true.

These days I increasingly think that the private motorcar should be banned inside the north circular* and the city pedestrianised from Archway to the imperial war museum, and from

Notting Hill Gate to the Tower. We have the public transport infrastructure to make this work.

*With exemptions for mobility issues.