Why tube strikes can improve Londoners' commutes

Strike special: We find the Lime parking bay with 411 bikes, explain why some tube lines are still running during a tube strike, and have the data on the Elizabeth line surge.

As we travelled around London during this week it became increasingly apparent that while “commuter chaos” is the term used by many news outlets to describe this tube strike, it might be better termed “commuter discomfort”.

We’re not saying that the strike isn’t highly disruptive and costly to the capital’s economy. Just ask all the people who were planning to go to Coldplay or Post Malone’s stadium gigs this week, or the (often lower paid) staff who have no choice but to travel to work by any means possible. But things felt different this time. A combination of many office workers being able to work from home, the enormous capacity of the still-running Elizabeth line, and an influx of Lime bike users are blunting the impact of strikes compared to previous rounds of industrial action.

All of this has big political implications for the capital. If tube strikes no longer disrupt London as much as they used to then the threat of further industrial action will give unions less leverage in negotiations. That’s something both Transport for London and the RMT will be pondering as they work out their next moves.

All of our journalism is made possible by our paying subscribers. We only publish our journalism when it’s ready — if you’re able to support our reporting about the capital then we really appreciate it.

A Cambridge professor explains why tube strikes cause Londoners to permanently improve their commutes.

This week’s tube strike is set to leave its mark on London, but perhaps not in a way that you might expect. Based on previous tube strikes, it’s expected that some of the people trying the Elizabeth line, London Overground, or Lime e-bikes for the first time this week will never go back to their old commute.

That’s according to research gathered by Professor Shaun Larcom of the University of Cambridge during a previous tube strike in 2014. He and his colleagues concluded that around 5% of London Underground commuters permanently changed their route to work following that year’s industrial action.

“A whole bunch of people were forced to experiment and a whole bunch of people seemed to find a better way to go to work,” Larcom, a professor of law, economics and institutions, told London Centric.

A decade ago Larcom and his colleagues Ferdinand Rauch and Tim Willems convinced Transport for London to share vast amounts of data from Oyster cards. This covered passengers travelling on the tube in the days before, during, and after the 2014 strike.

Because less than half of the network was affected by strike action that year, the academics had the researcher’s dream of a “control group” of passengers whose lives continued as normal and a strike-affected “treatment group” that were forced to seek alternative routes to work.

“As I understand it, it was John Snow in the cholera outbreak who came up with this statistical design,” said Larcom. “But it's what we would call a natural experiment where we have a real life situation that mirrors many of the attributes that we would like to see in a lab experiment.”

What their research concluded was that a notable number of strike-affected commuters were forced to change the main tube stations where they tapped in or out, then kept going to the new stations when the strike ended. People may have a chosen a route with fewer changes, or discovered a less crowded tube line that they preferred.

On a normal day commuters are put off trying new routes by “search costs”, explained Larcom. That refers to the time and effort and risk of a commuter trying a new route and getting it wrong: “You could get to work late.”

But during a strike people are forced to go through the experimental process regardless, and possibly with more understanding from their bosses: “It's a perfect opportunity if you've got the search costs anyway to use it as an opportunity as opposed to just an inconvenience.”

A similar effect was seen during the London Olympics in 2012, where stark warnings about transport chaos caused many residents of the capital to discover new ways of getting around.

Larcom says in some cases the new strike-induced routes saved commuters a substantial amount of time, potentially meaning the industrial action had done them a massive favour: “It did seem to suggest that people should have been searching more than they otherwise would.”

He also suggested a potentially permanent shift towards rental e-bikes could be one of the stories of this strike, although the lack of a control group would make it hard to tell: “We develop habits and ways of doing things but there's shocks that come along. Many of them are inconvenient and we don't really learn anything from them, but others [provide] an opportunity to experiment and find better ways of doing things.”

Why certain tube lines are still running during a tube strike.

If there’s one thing you wouldn’t expect during an all-lines tube strike, it’s a tube train on the Northern line. Yet that’s exactly what was happening on Tuesday, while chunks of the Metropolitan line are running on Thursday.

We’ve been talking to people to find out what’s going on.

In order to maximise the impact of the strike while also reducing the cost to workers (who go without pay on strike days) the RMT asks its members in different teams to strike on different days. This creates the effect of a ‘four-day strike’, without all RMT staff actually being off for all four days.

On Monday and Wednesday it was the turn of station staff and tube drivers to go on strike. On Tuesday and Thursday they were back at work, instead relying RMT members involved in signalling to maintain the strike for those two days.

Yet if enough non-unionised signallers turn up to work then the RMT drivers and station staff (plus employees in other unions that aren’t on strike) who turned up to work can’t simply down tools. As a result certain bits of the network may suddenly spring back to life when TfL managers judge there are sufficient staff to do so.

Transport for London finds it easier to operate above-ground London Underground stations in the suburbs with the bare minimum staff, while deep level stations have more stringent safety requirements so stayed closed. As a result you’re more likely to see tube services terminating early on the fringes of central London.

Is this the most crowded Lime bike parking bay in strike-hit London?

Bloomberg News is known for both its influential financial reporting and for paying British journalists far higher salaries than they can hope to get elsewhere. Yet despite its illustrious track record of scoops and hundreds of London-based journalists at its giant headquarters in the City of London, we may have found a story on Bloomberg’s literal doorstep.

Following a tip from a number of readers, we spent a drizzly afternoon trying to ascertain whether the e-bike parking bay opposite the organisation’s office near the Bank of England is The Most Crowded Lime Bike Parking Bay In Strike-Hit London.

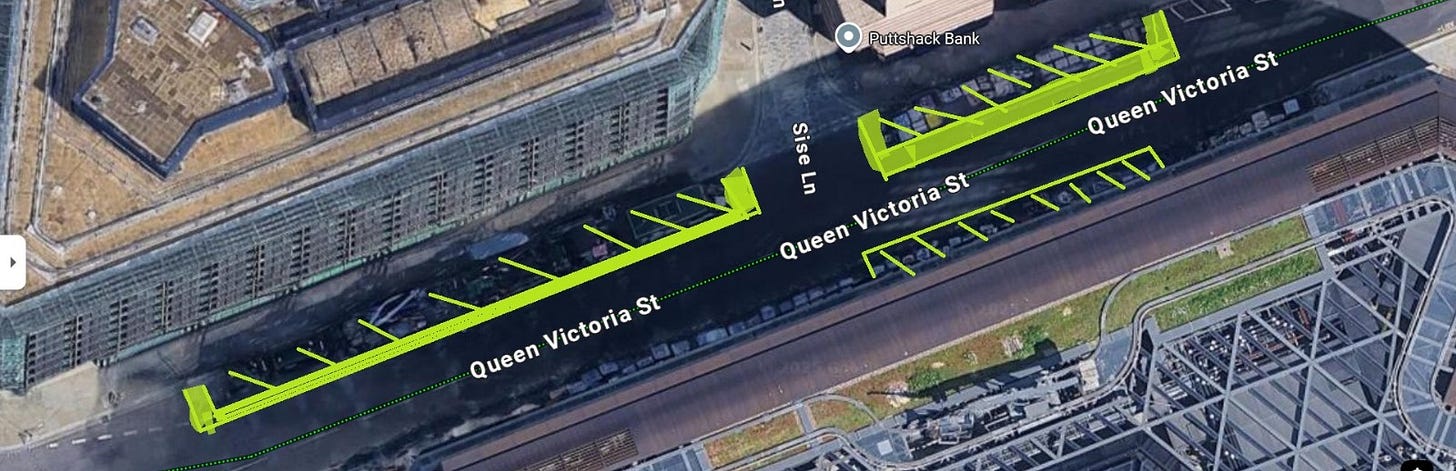

By combining traditional shoe-leather journalism techniques (a reporter standing in the rain using a clicker to count bicycles) we found this single parking area outside the Bloomberg office on Queen Victoria Street contained 415 Lime bikes (plus a further 35 Forest bikes) at lunchtime on Wednesday.

We then applied modern open source intelligence journalism techniques (drawing lines on Google Maps), took into account the straggler bikes dumped at each end, and found Bloomberg has 100 metres of pure Lime bike parking. Even Usain Bolt couldn’t sprint that distance in the time it would take you to buy a Lime pass. Although he’s possibly more of a Forest guy.

Data shows the Elizabeth line and Overground really are picking up the strain.

Transport for London has been releasing its own data on how many people have been travelling on its network, which show broadly stable patterns throughout the week. This is what they released on Wednesday:

The total number of people using the TfL network (as measured by the number of unique Oyster and contactless cards used) is down 24% compared to the same day last year.

Elizabeth Line passengers are up 26%.

London Overground passengers are up 20%.

Bus traffic is up 5%. (Although anecdotally we’ve seen a lot of drivers wave passengers on without tapping in).

Santander Cycle Hire is up 93% week-on-week.

What these figures suggest is that closing the London Underground has caused around a quarter of people to avoid using TfL services. While a large chunk of those people are office workers able have worked from home, many others have used non-TfL services such as Lime e-bikes, black cabs, Uber taxis, or walking from their National Rail station.

Most intriguing are the enormous surges in London Overground and Elizabeth line usage which, as you’ve heard above, could become permanent.

Are Lime bikes creating a state of Critical Mass for cycling in London?

There’s a manoeuvre we’ve taken to calling the “Lime bike wobble”. It’s that moment where an unsteady Londoner on a 35kg green rental e-bike starts to push away from the lights and the bike’s powerful electric boost kicks in just as the front wheel starts to jackknife. The effect, as the rider tries to retain control and move forwards, is a thrilling, terrifying, unpredictable mess.

This week hundreds of first-time riders have been doing the same move while heading to work, giving a chaotic energy to central London’s increasingly congested streets. One of those people was Clare, who we found locking a Lime bike up in the City of London: “Normally I go into Waterloo and take the Waterloo and City line but now I’ve been walking and then catching a Lime bike halfway along to get here every morning. It’s been quite nice and refreshing.”

The Lime Bike debate is a familiar one to Londoners, with the visceral hatred some feel for the way they block pavements mirroring the evangelism of some new users, and not always mutually exclusively. The elderly and disabled find them blocking pavements, while pedestrians can be infuriated by Lime’s minute-by-minute charging structure incentivising people to run red lights.

But the pro-Lime faction crosses traditional political divides. The Spectator this week carried a piece about how Lime bikes were “obviously unsafe” but only people who ”believe in the state as protector, nanny and moraliser” would want them banned. “Lime bikes set you free,” said the author.

The argument from the other side of the political tracks, as set out by the left-wing writer Dan Hancox in March, is that Lime bikes are a step towards a true Critical Mass event. In this telling, the streets of London are becoming so overrun with unpredictable rental e-bike riders that cars and other motor vehicles have little choice but to cede control of the road.

Lime is one of the biggest disruptors in how the capital gets around since Uber (which now owns 25% of Lime’s parent company) revolutionised London’s minicab business in the early 2010s. Lime has created a new privatised form of public transport with no regulation, well-documented safety concerns, dubious maintenance standards, little accountability, and an enormously receptive audience who are lapping it all up via £6.99 passes.

As one author, writing under the name Normal London Bloke, put it while reflecting on this week’s strike action:

…whilst it is easy to hate these things, we shouldn’t. Or at least, not only. Yes, the moment you mount it you are a participant in a bizarre public health experiment. A sweating panicked test pilot for a vehicle whose primary design feature appears to be launching its rider into the path of a lorry.

Because you see, against all odds, Lime has achieved what decades of green policy and cycling campaigns have failed to do: they have, through sheer obnoxious ubiquity, forcibly reclaimed swathes of tarmac for cyclists. They have made drivers see us.

So is this going to end any time soon?

The RMT union has hinted it would accept a deal that includes a half-hour reduction in working time, as the first step towards a 32-hour working week. Transport for London is saying it won’t budge an inch and can’t afford any reduction. As a result more strikes could be coming, while the future of ticket offices on the Elizabeth line could be another flashpoint for industrial action.

Mayor Sadiq Khan, who has largely stayed out of the talks between TfL and the union, told the London Assembly on Thursday that the “strikes are bad for London” and said he’s "confident that talks will resume once these strikes are over”.

Eddie Dempsey, the RMT’s general secretary, urged Khan to get directly involved: "Stop going on social media, invite us to the meeting, let's have a discussion, because I want to know what is going on in London. We take no pleasure in causing disruption but we make no apology for fighting for our members. So if the mayor has any sense, he will reach out to us.’

ASLEF, a separate union which represents a large number of London Underground drivers, has also been working towards a four day week. In a sideswipe at the different tactics of the RMT, one London ASLEF organiser told members last month: “It must be [the] first time in history that a trade union has called for a strike to prevent its members from having a shorter working week and more days off.”

Is this woman with a suitcase the most innovative use of a Lime bike during the strike?

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Answer: Yes, we’re pretty sure it is.

If you want to get in touch with London Centric then message us on WhatsApp or email — or click below to leave a comment.

I cycle from on the C4 into central London three times a week, and one of the things that was already evident but the strike highlight further, is that the cycle lanes built are already inadequate. They aren't wide enough for the volume of bikes using them during the peak (e.g. you can't overtake easily) and the light phases aren't long enough at certain junctions for the volume of bikes to get through.

Very interesting. I'd love to understand, in even more depth, how the RMT calculates the costs and benefits of actions like this. Barring concessions from TFL, what will they count as a win or a loss in terms of this action? What's the constraint on further strike actions from their point of view? Is it members not keen on losing more income, is it possible shifts in public opinion? What's the internal debate they're likely to be having about how to proceed? I know there are plenty of informed readers who might have some answers.