London's other sewage scandal

London Centric traces illegal sewage from a single polluting pipe on its toxic journey across the capital.

Today, as on most days, someone on an upmarket road in Crouch End will send untreated raw sewage out of their building and directly into the capital’s river system — and they might not even realise they’re doing it.

It’s just one of the thousands of properties across London that have their sewers plumbed directly into London’s ancient network of local streams and rivers. Experts say there could be tens of thousands more cases across the capital, collectively dispatching “Middle Ages levels of sewage” into the Thames.

For once, Thames Water aren’t the biggest villains in this lesser-known story of river pollution. Instead, it’s a potentially more troubling and hard-to-fix scandal that has largely gone under the radar. It’s caused by an ever-growing number of dodgy builders and DIY plumbers — and it’s a problem that threatens Sadiq Khan’s promise to clean up London’s rivers.

London Centric is telling one of the most overlooked pollution scandals in the country by chasing the output of a single illegal pipe on its journey across the capital, pieced together through dozens of environmental information requests.

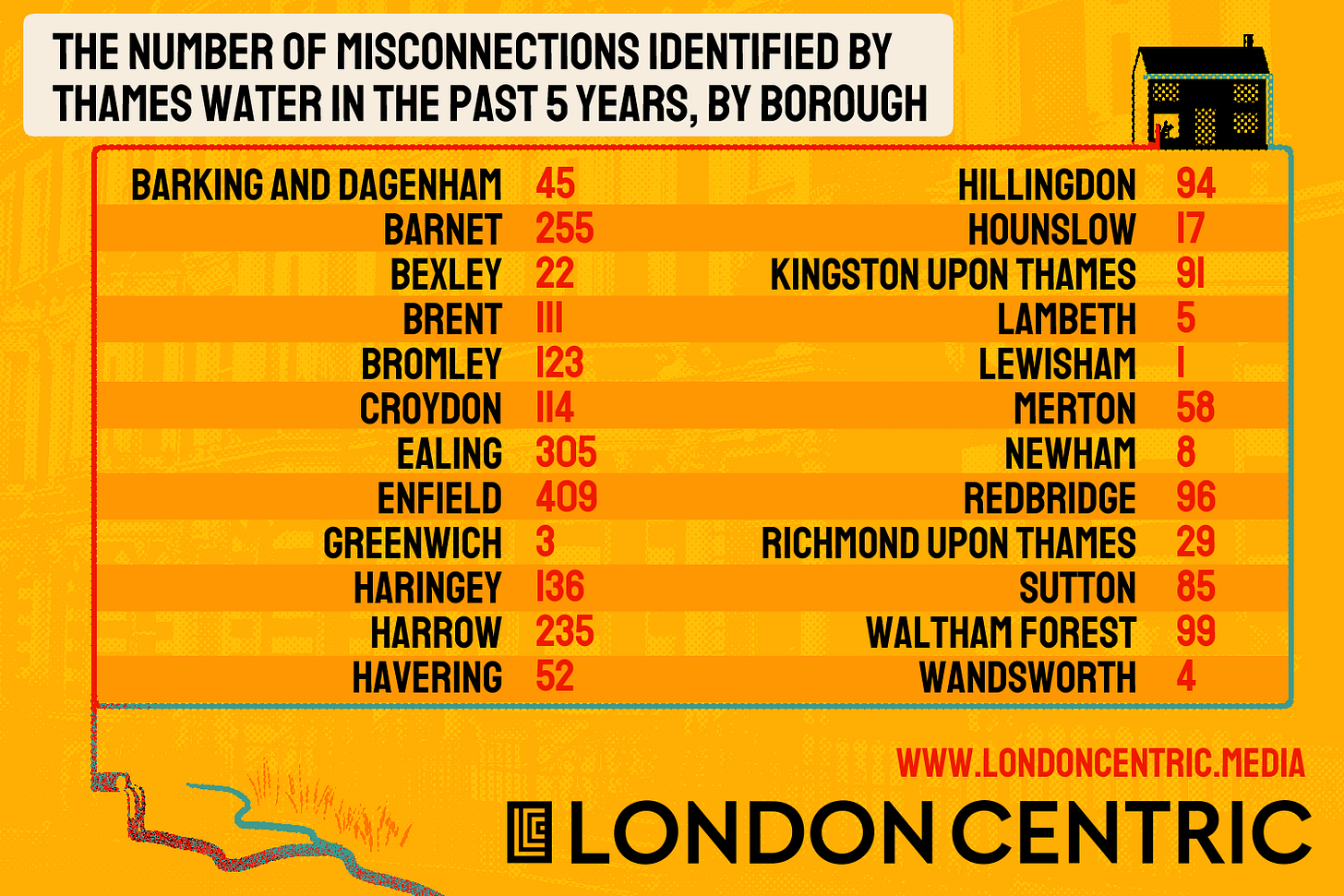

For the first time we’re also publishing figures showing how many similar cases are in each London borough — enabling you to see if your neighbours are contributing to the mess.

Words: Rachel Rees, Photography: Jennifer Forward-Hayter, Illustrations: Carly A-F, all commissioned by London Centric.

1. The scene of the crime: Park Road, Crouch End

Park Road is an upmarket street in Crouch End, in the shadow of Alexandra Palace, North London’s Victorian ‘palace of the people’. It is home to organic shops, wine bars, extensive playing fields, houses that sell for more than a million pounds — and a property that is a small part in one of the capital’s biggest sewage scandals.

Mass sewage discharges by the embattled Thames Water tend to hit the headlines. They take place when rainstorms overwhelm treatment plants, forcing the company to discharge untreated sewage directly into London’s rivers. The issue has become politically and environmentally toxic, symptomatic of how a privatised water industry has failed to invest in its infrastructure. Thames Water, with its rapidly-increasing bills and financial insecurity, also serves as an easy-to-hate target.

But Thames Water is not responsible for the Crouch End property polluting a park in Tottenham, nor the thousands of other properties across the capital that are also leaking raw sewage into local waterways.

Instead, the issue here is something called ‘misconnections’.

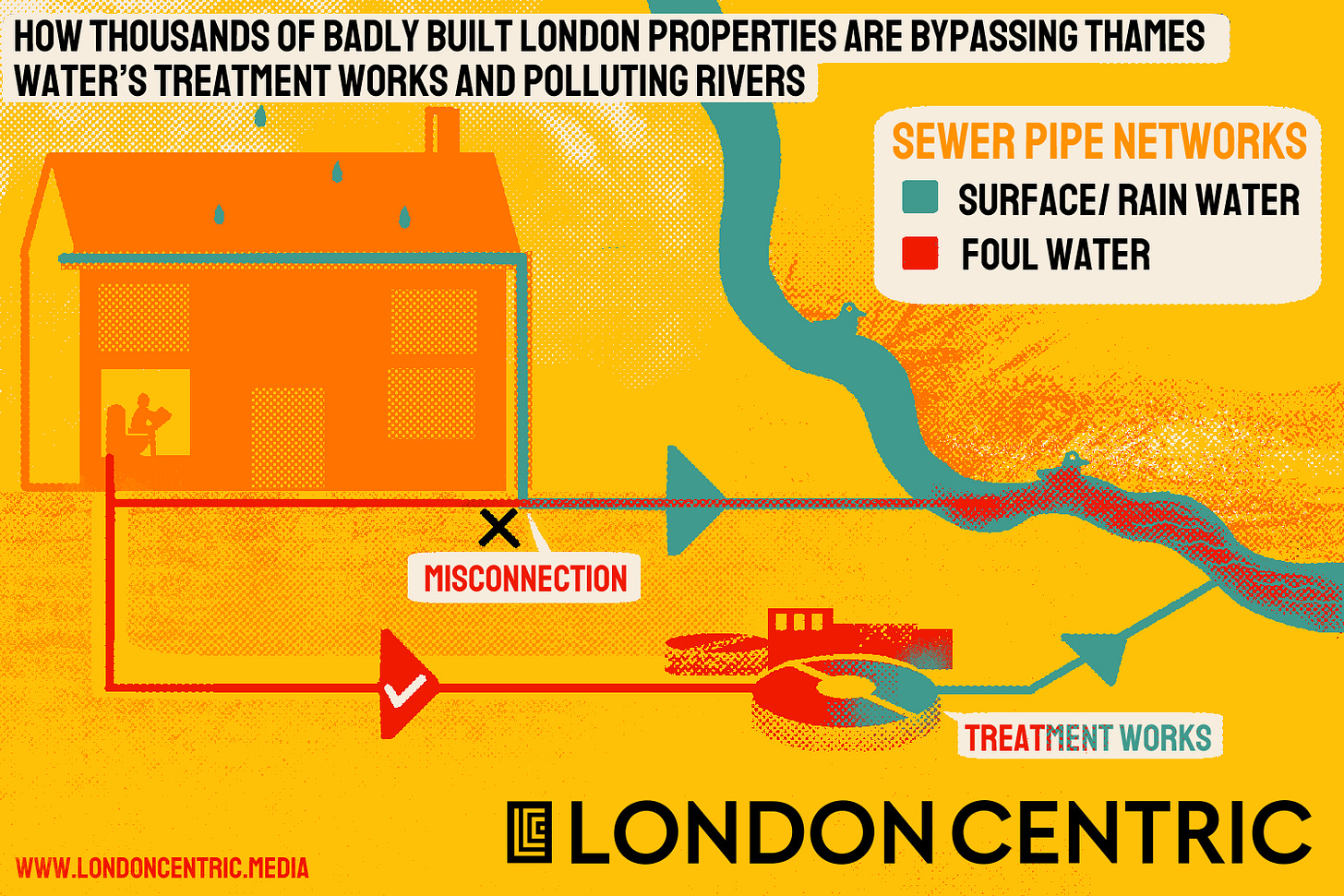

The majority of Greater London has two separate sewer networks.

One is a foul water sewer for household and commercial wastewater, which flows to a sewage treatment works. The other sewer is for rain from gutters, which is legally allowed to flow into local streams and rivers.

Misconnections occur when toilets and other appliances such as showers, sinks and washing machines are illegally plumbed into the sewer meant for rainwater. Sometimes it’s done on purpose by builders as a cost-cutting measure. Sometimes it’s done out of laziness. Sometimes it’s just pure ignorance.

According to a Freedom of Information request by London Centric, a property on Park Road is sending untreated wastewater into a rainwater pipe that runs directly into the River Moselle, an ancient local waterway flowing from Highgate to Tottenham, which has mostly been buried underground. Haringey council declined to identify the specific building causing the issue — but it was easy to see its impact further down the hill.

Give the gift of London Centric this Christmas — click here to buy a very different present for the person who has everything and support investigative local journalism.

2. The local park with “Middle Ages levels of raw, untreated sewage”

Around two miles east of Crouch End sits Lordship Recreation Ground, Tottenham’s biggest park. In this park at the bottom of a hill, the Moselle surfaces and flows close to the Broadwater Farm housing estate.

At this point the Moselle should consist of clear spring water mixed with some rainwater collected from gutters on domestic properties and roads. But untreated sewage from misconnected properties uphill in some of London’s most expensive areas, including on Park Road, is illegally flowing into the river.

As a result the stream is filled with used wet wipes, stringy sewage fungus, and other indications of human waste. Signs warn the public against swimming.

Theo Thomas, founder of the London Waterkeeper charity, said “persistent, chronic pollution” has made this stretch of river “essentially dead”. Water testing regularly finds high levels of ammonia, dissolved oxygen, and phosphate, all evidence of sewage. “What should be an amazing, high-quality blue and green space stinks. If you go in the summer, you will smell it before you see it.”

The pollution in this bit of the river can only be caused by misconnections, Thomas said: “If you’ve got something like 50 toilets and something like 150 washing machines coming in, that’s a lot of pollution. That’s Middle Ages levels of raw, untreated sewage coming in.”

At least two separate local primary schools have been found to be discharging sewage directly into this river due to misconnected pipes. At one point a single school was sending 90,000 litres of untreated wastewater directly into the river.

Volunteers from the Haringey Water Squad run regular clean-up sessions at the stream — but the pollution keeps coming, from misconnections both old and new.

“It’s an environmental social justice issue,” added Thomas, noting the wealth disparity between the leafy areas in which some of the misconnected properties are located, such as Crouch End and Muswell Hill, and the more deprived environs of the park in Tottenham. “The river is being damaged, and people’s ability to enjoy it is being damaged.”

3. The sewage enters the River Lea

The ancient River Moselle returns to its culvert and carries Crouch End’s misconnected waste past the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium. Near the wetlands west of Walthamstow it flows into the River Lea, which runs from Bedfordshire down to the Thames.

The Lea is typically filled with kayakers, rowers — and sewage.

This stretch of the river faces a “chronic, ongoing pollution from misconnections”, warned Thomas, from the Waterkeeper charity. “It’s a constant inflow — not just from the Moselle, but from other rivers coming in.”

Rob Gray, head of west London river charity FORCE, previously told London Centric that misconnections “might be the largest issue in terms of river pollution for London”. Unlike the “sharp pain” when an overwhelmed Thames Water treatment plant discharges vast quantities of sewage, misconnected properties cause a constant influx of pollution into the capital’s waterways, creating a “quiet, steady, background poisoning”.

The full scale of the issue is hard to quantify. Finding misconnections is a time-intensive operation requiring volunteers to wade up polluted waterways in search of outfalls, before Thames Water tries to trace pollution sources to individual properties.

According to an internal Thames Water investigation seen by London Centric, more than 3,500 misconnections have been resolved across London since 2020, — though experts estimate the real figures could be much higher.

Thames Water has previously estimated that as many as 1 in 10 properties are misconnected across the area it covers, inhabited by around a quarter of the UK’s population. Martin Beattie, vice president and co-founder of the National Association of Drainage Contractors, told us there could be up to 50,000 misconnections across London and the Home Counties.

4. The polluted water drifts through Hackney Marshes and the Olympic Park

In the Lea, pollution from misconnections such as the Crouch End property mixes with sewage from hundreds of other misconnections. The toxic mix then flows through swathes of east London, passing areas including Clapton, Hackney Wick, and Stratford. This river cuts through green spaces such as Hackney Marshes — where many Londoners defy signs and sewage to swim on hot days — and the Olympic Park.

When Thames Water find misconnections, they contact property owners, who are liable for fixing them. But resolution can be expensive and frustrating. If owners do not fix the problem voluntarily, cases are referred to local councils, whose responsibility it is to ensure that misconnections are fixed and who can prosecute non-compliant property owners.

London Centric can reveal the borough-by-borough breakdown of the thousands of misconnections identified by Thames Water over the past five years, based on an Environmental Information Request we submitted to the company.

These only include the new misconnections identified in the time period and not those discovered earlier but which homeowners or councils have failed to resolve.

Haringey has 161 live identified misconnection cases, the highest of any London borough. One property in the borough has been continually releasing sewage for more than 16 years with no action. Other particularly impacted boroughs include Barnet, Enfield, Ealing, and Harrow.

“It’s not clear that Haringey [council] is putting the resources into dealing with these misconnections,” said John Miles, chair of the local, volunteer-led Haringey Water Squad. He described the borough as consistently “bottom of the league” among London authorities.

A Haringey council spokesperson said: “We take seriously any pollution of our local watercourses through contamination and the impact it has on our residents and the environment. Thames Water are responsible for the sewage infrastructure in London and have the power to prevent and stop pollution from happening, which includes taking action when misconnections are identified.

“We work alongside Thames Water to investigate and get those responsible to reconnect their drainage systems when misconnections occur in private properties.”

5. The sewage from Crouch End finally enters the River Thames across the road from Sadiq Khan’s office.

Wastewater from the Park Road property, along with hundreds of other misconnections across north and east London, ultimately reaches the River Thames at Bow Creek.

It’s then disgorged into the capital’s main waterway opposite the O2 and just a few hundreds metres away from Sadiq Khan’s office at City Hall.

Lack of awareness about misconnections is one of the biggest hurdles in tackling London’s secret sewage crisis. Rhiannon England, one of the volunteers who regularly tests the Moselle Brook for pollution, said that before joining the group she’d never heard of the term. “I doubt anyone knows about misconnections,” she said, calling on authorities like Khan to add the topic to the curriculum in London schools.

Sadiq Khan’s spokesperson emphasised the mayor’s commitment to working with councils and other organisations to resolve misconnections. “This is about making our rivers something that every Londoner can be proud of as we continue building a greener, fairer London for everyone.

Thames Water’s unpopularity with the public — its mountain of debt, high bills, and fault-filled infrastructure — does not help public attitudes towards a problem that is hard to comprehend.

Yet there is some hope. When London Centric first reported on this issue back in April, we publicly named seven blocks of flats that had been sending untreated sewage into the rivers of west London. In late November, we received a picture of major construction work taking place outside one of the buildings we’d featured in Ealing. After a decade of sending sewage into the local watercourse, the pipes will soon be running in the right direction.

If you want to support London Centric’s work please help us by spreading the word that we’re trying to do journalism the right way. Forward our emails, share links to our stories in your WhatsApp groups and on social media, and encourage your friends to join our mailing list. Paying subscribers fund all of our journalism.

If you’re willing, why not buy a Christmas gift subscription for a friend who might appreciate it?

I thought people might be interested in how a story such as this one comes together... back in April we published a piece looking at the specific issue of misconnections in one corner of London. But the volunteers working on the River Brent and River Crane in west London, who have been doing the leading work highlighting this issue, say it was hard to make people comprehend the scale of the problem.

The issue is you just see stories about "thousands of properties leaking sewage" and none it feels real.

I challenged Rachel Rees, who spent most of this year working for London Centric, to find a single example of a misconnected pipe and trace its journey through the capital. This became one of the most infuriating projects we've done. Endless formal requests for information, tracing underground rivers, trying to convince authorities that we are trying to highlight an issue and get individuals to confront it. She had to put up with constant nagging from me to keep going. Eventually she found this location in Crouch End and managed to follow its journey across north and east London.

All in all this was an absolutely crazy amount of work over eight months to bring this single story to life.

Rachel has since left to join a niche news publication called the "Financial Times", having picking up a nomination for young journalist of the year for her work with London Centric. So this is probably her final byline here — and it's one of those that I'm really proud to publish.

Great reporting thank you! It‘s exactly stories like this one which show why London needs proper news reporting.