The man who wants to knock down the London cinema he saved

Plus: Exactly how loud is Mighty Hoopla — and when will London get any money to expand the tube network?

We’ve been busy at London Centric working on some chunky investigations that are coming up over the next few weeks.

While we keep our lawyers busy, we’ve got a few stories for you today, including the curious story about a man who set up a beloved indie cinema in east London that was once named the best in the country — but now wants to knock it down, taking on outraged locals.

Scroll to the end for the row over the Genesis cinema, or first read a selection of other bits from across the capital.

So, Rachel Reeves, what does London get?

This is, very roughly, how government communications works: There’s a calendar ‘grid’ in Downing Street and most days there’s a single story on this grid that the government really wants to hammer home on as many media outlets as possible.

To achieve this a cabinet member will usually give a speech, tour the nation’s TV and radio stations to discuss the speech, and journalists will be pre-briefed with a fresh ‘news line’ from the speech.

Sometimes it’s “defence day” and sometimes it’s “immigration day”. Yesterday it was the turn of “we’re going to spend loads of money on transport outside of London day”. Chancellor Rachel Reeves said the capital’s public transport network “helps explain London’s global success, and also its advantage over other UK cities” and therefore she wants to invest billions of pounds in schemes across the rest of England to bring them up to speed.

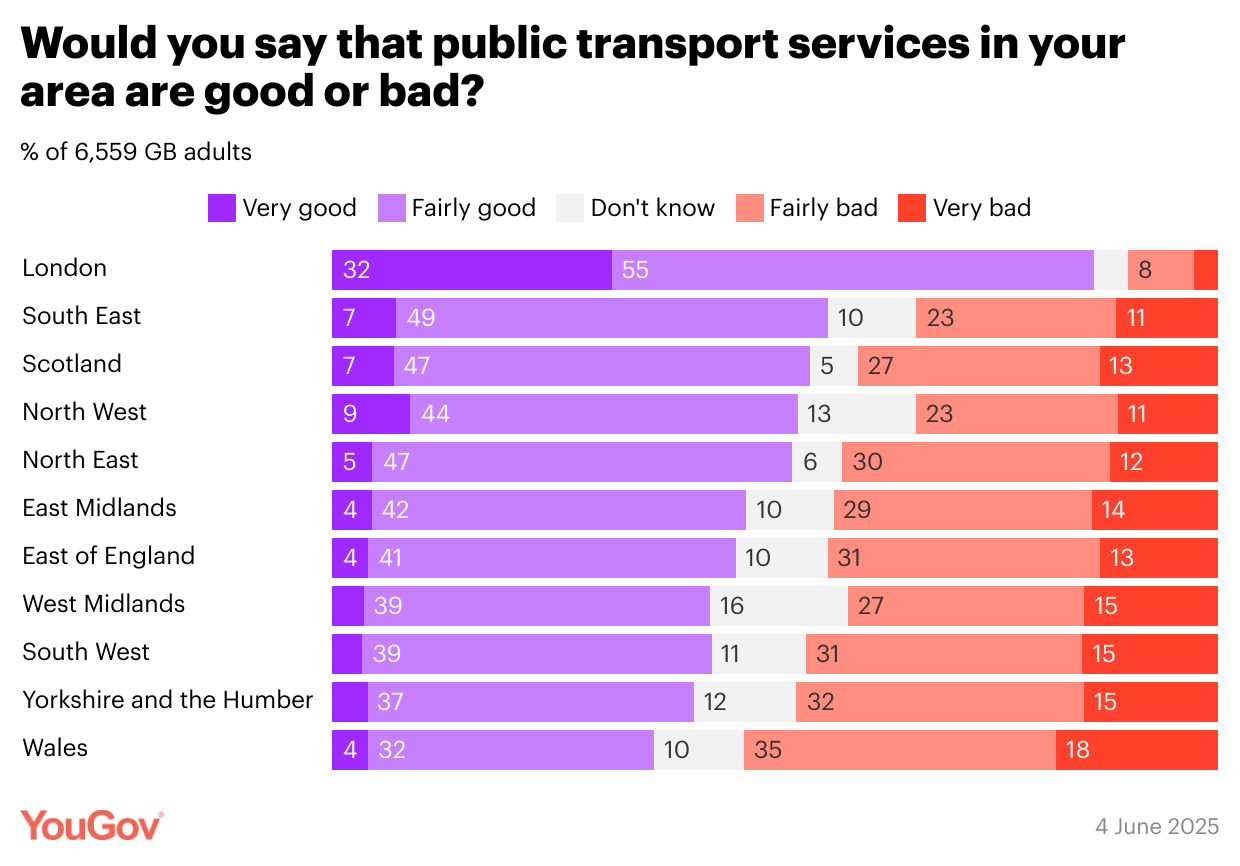

It’s hard to disagree with this argument; when we talked with Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham he complained he is only just gaining the powers that London has enjoyed for years. Over the last decade we’ve seen the expansion of the Overground, the arrival of the Elizabeth line, and even the odd bit of London Underground expansion. The capital’s residents also know they have it better than everyone else. Just look at this new poll from YouGov.

The growing worry among London’s politicians is this: What if the investment in the rest of the UK comes at the expense of investment in the capital, rather than in addition to it? Large transport schemes take decades to be delivered and almost everything that has been opened in London in the last few years had its genesis in the late 2000s or early 2010s. The pipeline for big, funded projects in the capital is largely dry.

A Labour government working with a Labour mayor was supposed to avoid the issues of the past, such as when Conservative minister Chris Grayling blocked a near-complete plan to hand the Southeastern rail network over to Transport for London. This was, he cheerfully admitted in a private letter, in order to keep it “out of the clutches” of a Labour mayor. But even now, a decade later, with 59 of the capital’s 75 MPs belonging to the Labour party, the new government has still not handed over control.

Sadiq Khan has limited ability to raise cash directly and push ahead on big projects, so has to resort to asking central government for money on a case-by-case basis. There’s some cause for optimism on this front: The Docklands Light Railway extension under the river to Thamesmead might happen as it will unlock housing development, while TfL is hopeful of a longer-term funding deal that will enable it to plan further in advance.

But right now there’s no indication of funding for major projects such as the much-delayed Bakerloo line extension to Lewisham, let alone Crossrail 2 from Wimbledon to Hackney. Even if funding for these was announced by Reeves in next Wednesday’s spending review, a child starting school in London this year will be an adult before they have any chance of travelling on those lines.

Talking of TfL, the organisation has put out the first stats on what happened since it opened the Silvertown tunnel. As London Centric spotted back in April, the ancient free ferry over the Thames at Woolwich has been overwhelmed with freeloaders and the Sat Nav dependent, with TfL saying an extra 1,800 vehicles a day are using the toll-free crossing.

London Centric’s reporting is paid for by people who are willing to support traditional, on-the-ground journalism about the capital. If you haven’t joined already and are willing to become a paid subscriber then your support is much appreciated.

Things that aren’t so hot in London right now: Beyoncé. Tickets for her six nights at Tottenham Stadium this month are very much not sold out, with hundreds of seats still available for tonight’s gig.

Is Mighty Hoopla actually as noisy as people say?

Last week data scientist Ricky Nathvani approached London Centric with a proposition, following our coverage of music festivals in the capital’s parks. One of the common complaints from residents regards the loud noise caused by hosting gigs in a residential area.

The problem is, while the festival organisers and council do their own noise monitoring, they are reluctant to share the data with the public.

Nathvani offered to do his own independent checks — and see whether the festival promoters are telling the truth.

Last Saturday tens of thousands of people spent the day in Brockwell Park at Mighty Hoopla watching the likes of Ciara, the A*Teens, and Daniel Bedingfield. What they didn’t know was that Nathvani was outside, spending 11 hours cycling around the perimeter fence taking sound readings for the benefit of London Centric readers.

This is what he found, in his own words:

One of the recurring complaints against Mighty Hoopla is its supposedly unbearable noise. Residents quoted by the BBC in 2023 described the noise as "horrendously bad” while this year one local told the Telegraph that Mighty Hoopla's noise was "a kind of hell". But every year the promoters say that it and Lambeth Council use independent noise consultants to actively monitor noise levels and that the festival never breaches the legal noise guidelines.

The threshold, commonly used for musical festivals in the UK is, simply speaking, that it shouldn't exceed the continuous equivalent of 75 A-weighted decibels over the course of fifteen minutes. This is the equivalent of something like having a vacuum cleaner on, or standing near a busy motorway.

Armed with a Class-2 sound-level meter and a tripod, I set out to recreate the noise consultant's monitoring campaign, in real time, on the Saturday of Mighty Hoopla, measuring the exact same metrics in the same spots using a similar protocol to the consultants to check how bad the noise really got.

I may have done too good a job. On six occasions I bumped into the actual noise consultants hired by the festival who were recording noise in the exact same time and place. They found it difficult to believe a random, dedicated citizen with no skin in the game would be doing something so insane on a Saturday, but entertained me nonetheless, despite being convinced I was a spy sent by anti-festival campaigners.

They also informed me that the daily number of complaints for Brockwell Live events this year is very consistent with any event of a similar size in London (between 20 and 50 a day).

Despite using a cheaper, slightly less accurate sensor, my data is openly available, so here’s the scoop: For the overwhelming majority of Saturday’s Mighty Hoopla, at all locations, the noise didn’t exceed Lambeth’s thresholds and in most cases it didn’t even get close to the 75 decibel legal threshold. The only possible exception may have been for residents closest to the main stage during Ciara’s set at 9.30pm but that was just over the limit on the very edge of the park.

If you live any further away, there’s virtually no chance the legal noise thresholds were breached. Admittedly, the noise was probably audible for some distance around and if you were trying to put a baby to sleep and live on the edge of the park, I can definitely believe it was a struggle.

On a technical level “horrendously bad” and “a kind of hell” may be an exaggeration. But one of the professional sound consultants I spoke to on the day summed up the real issue: “Often, with these events, we find that the level of noise isn’t the root cause of the complaint compared to the moral indignation of being reminded that this sort of event is happening in a public space at all.”

In further everything-is-connected-in-London news, several of the Brockwell Park festivals are put on by festival promoter Superstruct who are, in turn, part-owned by Wall Street investment firm KKR.

Until this week, KKR was the preferred bidder for troubled Thames Water — until the company pulled out of the deal. When it comes to exploiting public services, it appears KKR (made famous in the Wall Street film Barbarians at the Gate) thinks there’s more profit in the capital’s parks than the capital’s water supply.

Our investigation into London’s dodgy 5G signal hit a nerve, with a general sense of exasperation that the capital’s phone networks over-promise. A common complaint was people who have travelled to some of the remotest parts of the world saying they had better data connection in the Arctic Circle or in remote deserts than they do in Trafalgar Square.

The piece was also shared by Money Saving Expert Martin Lewis who gave the sort of endorsement that makes it all worthwhile.

One well-connected source involved in setting the standards for 5G got in touch to suggest that the problem is partly due to phone manufacturers such as Apple failing to represent the reality of the capital’s overwhelmed phone network.

They said: “The standard says that there should be two different types of 5G icon. One for when it is being used, and one for when it is available but not used. The choice of the icon design is left to the individual handset manufacturers. Similarly there is no standard for how many bars you get at a particular signal strength. And just because there is a strong signal it doesn't necessarily mean there is the capacity in the radio networks. And even if the radio networks can cope it may be that the connection between the base station and the rest of the network is overwhelmed.”

They called on the telecoms regulator to do more to be honest with Londoners about the real state of the capital’s phone network: “Ofcom only tests the signal strength and then assumes everything else is OK.”

The man who wants to knock down the cinema he saved.

By Sophie Wilkinson and Rachel Rees

It’s a familiar story in modern London: a beloved cultural venue is under threat from redevelopment and locals are rallying around to save it from the wrecking ball before it is turned into more student accommodation.

But the dynamics of the fight over the Genesis cinema in east London differ starkly from the capital’s other cultural cause célèbre, the Prince Charles Cinema – where community pressure appears to have saved the venue from potential closure at the hands of its notorious landlord, Asif Aziz.

In the case of the Genesis, a family-run five-screener near Whitechapel station once dubbed the country’s best cinema, the man campaigning for its demolition is the same person who turned it into a cult destination.

Tyrone Walker-Hebborn was an electrician and roofer from the East End when he bought the cinema in 1999. The reopening event, after it had been derelict for years, featured EastEnders star Barbara Windsor. Nowadays it’s the sort of indie cinema that hosts festivals, a film about female bodybuilders for a queer wrestling club’s international women’s day commemorations, or a panel talk about migration hooked to Paddington in Peru.

Now 60, Walker-Hebborn told London Centric that he has no choice but to knock it down and start again: “If we don’t do this development, I don’t know how we’re going to survive”.

Earlier this year Walker-Hebborn submitted plans to Tower Hamlets council to demolish the existing Art Deco building and construct 291 units of student accommodation with a smaller cinema in the basement. All of this raises questions about what actually matters about a historic cinema. Is it the atmosphere and its sense of place — or is it having somewhere on your local high street that still offers the ability to watch new films on a big screen?

The current building, next to the Wickhams department store with its infamous gap caused by a stubborn jeweller, is a local landmark. The Genesis, which shows traditional blockbusters alongside cult favourites at just £2.50 a pop, has many fierce fans. It has a rich history – although the current building was built in 1939, the site had been a venue for almost a century before that, hosting entertainment icons like Charlie Chaplin and Laurel & Hardy. Lusby’s Music Hall and Temple of Varieties opened in 1868, and it first became a cinema in 1912, as the Empire, then the ABC and the Coronet.

But now Genesis is struggling in the wake of a ruthless onslaught of lockdowns, Hollywood strikes, the cost of living crisis, and the ever-rising popularity of streaming. Walker-Hebborn, who owns the freehold of the site and therefore stands to benefit from the redevelopment, claimed that the cinema had lost £10m over the past four years, with business still 30% below 2019 levels. “We are in a very, very difficult position,” he said, citing the recent closure of cinemas owned by Cineworld and Empire: “I’m not going to let that happen to Genesis.”

Planning documents submitted by a Northern Irish property developer state that the Genesis Cinema “facility/brand” will be at the heart of the plans, even though the cinema capacity will drop from the current 956 seats to 449.

The planning application also claimed that other options, like converting the existing site into three screens, a casino or mini-golf venue, were explored but “the existing building and cinema use are redundant”. It concluded: “No viable retention scenario was identified… the only way to retain the cinema function on site is through comprehensive redevelopment”.

Walker-Hebborn told London Centric that this family-run and owned site, once prosperous, is struggling: “My dad always taught me to put a bit away for a rainy day, we’ve had a rainy four years.”

“Realistically, to bring the building back up to spec will take an investment of between three and five million pounds". In the last few months, ticket sales have dipped, he explained, meaning the cinema is losing £10,000-£15,000 a week. “We’re in a really tricky position”.

The plans have come as a surprise to some locals, not least those signing a Change.org petition which states redevelopment would remove an “important link to our city's cultural heritage” and replace it with an “imposing development which makes a mockery of the local environment”.

But in a stark comparison to how these things usually play out at cultural venues, the Genesis Cinema’s Instagram page has responded by urging followers to “NOT SIGN THIS FALSE PETITION!”. Reader comments on this post have been turned off, Walker-Hebborn says, because “it was so vicious on there, such a poisonous place, social media”, and he suggests that the petition was boosted by a neighbour who opposes the construction, rather than a cinema fan.

Historic England also warned against the demolition of the existing building, saying “the Genesis Cinema is an important and valued historic East End establishment which has been lovingly restored by the current owner. Its demolition would be a sad loss to the community” and would “cause harm”. As part of its mitigation, the developer has suggested that retaining a cinema on site will “balance the harm of demolishing the existing building”.

The redevelopment plans present a conundrum. Should the cinema stay as it is, the 1930s design retained, at the risk of continued decline as it continues to feel the effects of Netflix and the cost of living crisis? Or should punters accept the venue being closed for five years while it’s redeveloped into a newer, smaller cinema?

Walker-Hebborn promised London Centric that redevelopment is a good compromise, that it would have been “much easier and more profitable” to just go with the various offers of turning the entire site into luxury flats, cinema be damned.

He insisted: “It’s not a way for me to develop the cinema. It’s a way for me to futureproof the cinema.”

Got a story for London Centric? Get in touch via WhatsApp or email, or leave a comment.

It's so refreshing to have local journalism that doesn't automatically back the NIMBY anti-development, anti-fun agenda. There is noise from my local park during events but for an inner city area it's not particularly noticable unless you listen for it. The evangelical church next door is MUCH nosier! Likewise, I have been to Genesis but completely get the point of the redevelopment - that bit of Whitechapel is already a wonderful architectural mess so I can't see this being an aesthetic problem. I'd rather knock down the building and keep a cinema

Thank you Ricky Nathvani! In a debate marred by lack of transparency (mostly on the part of Lambeth council IMHO), open data and code is such a breath of fresh air.