Why Omaze is giving away London's most expensive council house in a raffle

Shakespeare, social housing, and influencers: What does a prize draw for a Georgian town house near Borough Market say about the state of the capital's property market?

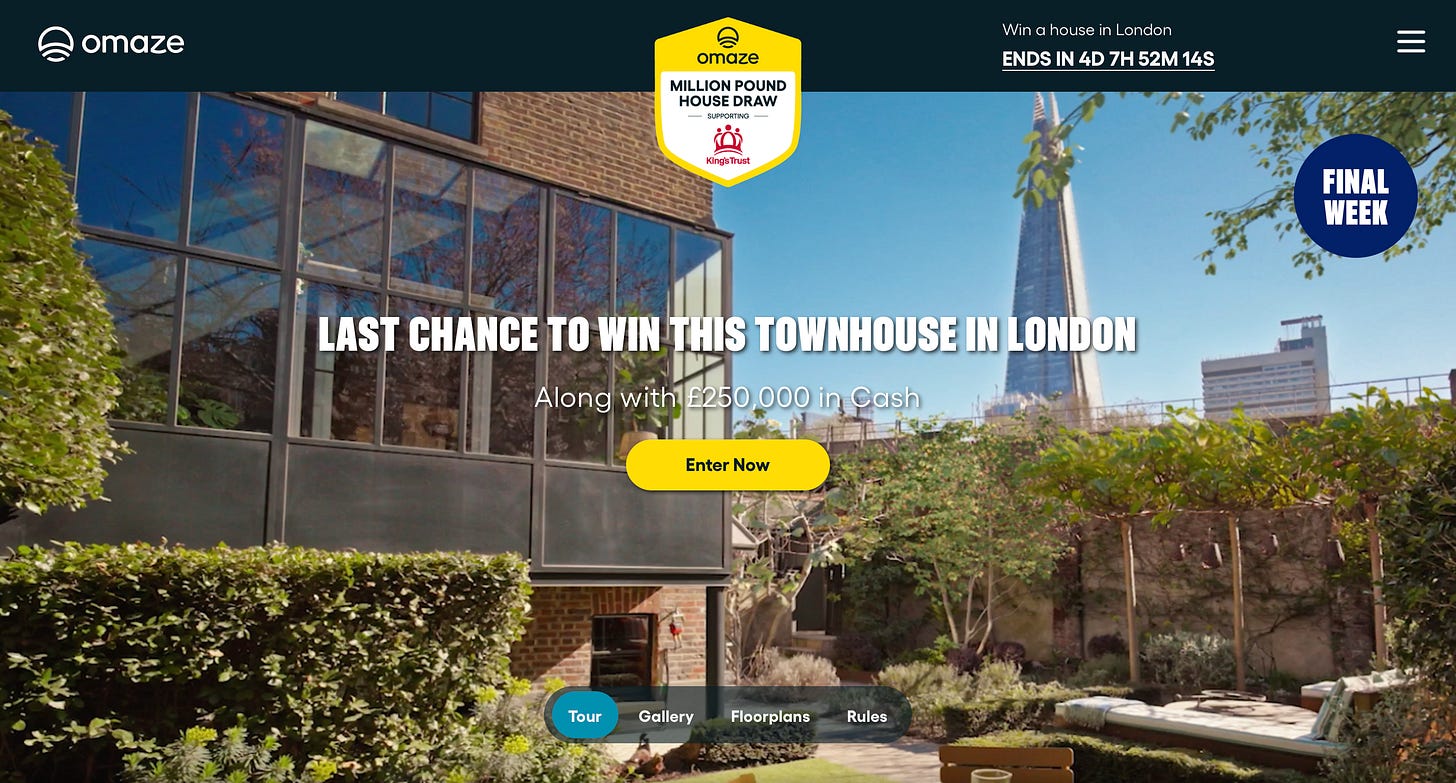

Is an artfully-lit Georgian townhouse near Borough Market following you around the internet?

If you’re a Londoner who has spent any time on social media over the last few weeks, there’s a good chance that adverts for 21 Park Street have been all over your Instagram or Facebook feed. The four bedroom house is described as being worth “over £4.5m” by Omaze, the for-profit company that has become a British cultural phenomenon by giving away properties in an online prize draw.

Better known as “Take Courage House”, due to the brewery ghost sign on its wall, the “breathtaking” home could be yours by next week — so long as you buy a raffle ticket by Sunday. Encouraged by a legion of paid influencers, it’s expected that more than a million Britons have already entered the competition for the London house.

London Centric estimates around £25m will be spent on tickets for the London house and the odds of winning are, in the most optimistic scenario, around one in 37.5 million — about the same chance as winning the National Lottery jackpot. But behind this very modern chapter in its long life, 21 Park Street is a property that tells the tale of the capital’s complex and changing housing story in a remarkable way.

Just over a decade ago the tenants were very different: this was a council house, allocated for people who were judged to be in need of a place to live. Back then it was a different sort of lottery — the council housing waiting list — that decided who got to live in one of London’s most desirable homes.

In 2013 squatters occupied the property, declaring Southwark council’s decision to sell the house to a property developer as “social cleansing”. The house briefly became a national cause célèbre, prompting soul-searching in national newspapers over London’s council house stock and which people the capital should belong to.

London Centric has spoken to individuals involved in the sale of what has become one of social media’s most famous properties. We wanted to know: How did Omaze end up giving away an ex-council house in a raffle? Is 21 Park Street really worth the £4.5m they claim? And is the politician who authorised the council’s sale of the property now buying Omaze tickets in the hope of winning it for himself?

This is a members’ only story, filled with details about one of London’s most intriguing homes and the people involved in its sale. If you want to keep reading and aren’t already a London Centric subscriber, either take out a free trial or join now for 25% off.

“That’s the way to manifest stuff.”

When London Centric visited 21 Park Street on Tuesday afternoon there was a steady stream of hopeful entrants in the Omaze draw who were visiting the building. All of them sincerely believed it would be in their possession by this time next week.

Kim Kraus-Walker, 55, was posing outside the house for a selfie as part of the “manifestation” process she is going through in the hope of securing victory. She explained this involved the idea that thoughts and positive energy can be turned into reality: “I’m doing my manifestation meditations every night. I’m imagining winning it. I’m imagining getting that phone call. That’s the way to manifest stuff.”

A firm believer in destiny, she is outside 21 Park Street to channel positive vibes: “I wanted to take a selfie and send it to my other half and say ‘LOOK! I’M OUTSIDE OUR NEW HOUSE!’”

Her optimism is infectious but — just like everyone London Centric spoke to outside the property — she is worn down by her lack of housing security in the capital. Kraus-Walker is privately renting a one-bed flat in Croydon with her partner and says she has no pension of note. Instead, she is pinning her hopes for a happy retirement on winning a home through a monthly subscription to Omaze which gives her 200 tickets in return for £25.

Manifestation has its rules. She is happy to have her photo taken but insists it cannot appear in this publication prior to the draw closing on Sunday night, in case this leads to irate London Centric readers thinking it’s a stitch-up: “What if I win it? It’s going to look like a fix!”

Like everyone else we spoke to, she has already pored over the floor plans and worked out which bits she’ll occupy and which she’ll rent out on Airbnb. In the era where browsing Rightmove is a national hobby and in a city where a deposit is financially a pipe dream for many, entering a raffle makes as much sense as anything else when it comes to housing in London: “This would give me the freedom to travel, which is something I want to do. I want to have a nice rest of my life. I still feel young. What a great place to entertain and have friends.”

As we talk we’re interrupted by Roland, who was also scoping out his future home after buying £100 worth of tickets. A 49-year-old chef who now lives in Copenhagen, he has already estimated how much it will cost him to run the property and is planning to let out parts of it, put in a test kitchen and perhaps have a podcast studio.

Roland grew up in the capital with two siblings but all have had to move out due to property prices. This Omaze prize draw represents hope of his family returning to their home city: “I am from London and I've always dreamed of living in London and I know this area very well, but I can't afford to live in London. So I've had to move out of London. My sister lives in Wales, and my brother lives in Essex. It’s tragic.”

Before speeding off in her white VW Golf, Kraus-Walker insists on taking London Centric’s phone number so she can invite us to next week’s housewarming party.

“It does look amazing, doesn’t it?” she said, taking a final glance at her intended future home.

“We are a diverse and mixed community”

To understand the history of 21 Park Street you need to go back to when William Shakespeare would have walked past the site on the way to the Globe theatre, which stood a few hundred metres away. In 1616, the same year that the playwright died, a brewery was opened next to his most famous playhouse.

The business was rebuilt over several centuries with investment from the Barclay banking family, enabling it to claim the title of the world’s largest brewery by volume. In the 1820s the company decided to build a pair of fine houses for the management by the entrance to the brewery; these became 21 and 23 Park Street. According to the bank’s official history, visitors who came to admire the modernised brewery and would have passed by the houses included French leader Napoleon III, German statesman Otto von Bismarck and the Italian general Giuseppe Garibaldi. The houses were used as accommodation and then offices for the next 150 years, the brewery eventually being owned by Courage.

In the middle of the 20th century this part of inner London was still dominated by industry, with the future Tate Modern still an active power station, burning vast amounts of oil in the middle of the capital. When the American actor Sam Wanamaker, father of Zoe, paid a pilgrimage to the site of the Globe during this period he was shocked to find the bard’s theatre was buried under a brewery. He spent the rest of his life campaigning for a reconstruction of the theatre to be built nearby, which is now Shakespeare’s Globe. In an echo of future battles over the Omaze house, he had to face down legal challenges from local housing activists who felt the riverside land should be used for homes.

When the brewery finally closed in 1981 its site was bought for development into council housing. Most of the area was turned into the low-rise Park Street council estate, a slice of suburban homes with ample car parking in Zone 1. Few parts of the brewery were retained, other than the Anchor pub on the Thames and a small number of listed Georgian houses on Park Street.

While the stereotype of a council house is a 20th century purpose-built building, in many parts of inner London rows of Victorian houses that would be worth over a million pounds each on the open market are still owned by local councils, saved from the wrecking ball in the 1960s and 70s. With 21 Park Street and its neighbours legally protected from redevelopment, they became council houses at the same time that Park Street was developed.

“We have to have mixed communities,” says the local Liberal Democrat councillor Victor Chamberlain, who has fought council house sell-offs in the area. “Social housing has provided that ability for all people to live together. It is amazing that we are in central London but we are a diverse and mixed community.”

“Elements of the building that were in a state of collapse”

By 2013 central London had been through multiple rounds of house price explosions while at the same time austerity was undermining council budgets.

Labour-run Southwark council looked at the poor condition of 21 Park Street and its twin house at 23 Park Street, realised they were worth millions of pounds, and decided the best policy was to sell them. What had once been an undesirable corner of the capital was now undergoing a property boom and the local authority argued it would be better-off cashing in than repairing them.

“It was a derelict building that the council couldn’t bring back into use as a council home,” recalls Labour councillor Richard Livingstone, who ultimately oversaw the sale. “As I understand it there were elements of the building that were in a state of collapse, there will have been a substantial amount of work done to it.”

Southwark council saw the deal as a slam-dunk: Two expensive Georgian properties requiring enormous investment would be sold and the millions of pounds raised would be used to build “20 new council homes”.

Livingstone recalls the argument: “It’s a difficult choice, it’s not where Southwark would have liked to have been, but it’s the least worst choice available to the council in terms of providing the number of homes that are available.”

What they hadn’t bargained for was the opposition from housing activists, who saw the sale of the properties as an immoral act in a borough where tens of thousands of people were on the housing waiting list. Several dozen people broke into 21 Park Street and squatted the property, unfurling banners reading “Stop Social Cleansing” and “Homes For All” from the same windows where, this year, perky property influencers have filmed themselves urging people to buy Omaze tickets.

A spokeswoman for the protest, bike mechanic Kate Sheldon, told the Evening Standard at the time: “The borough has massive housing needs and it's madness to sell off the public housing. We can't take Southwark Council's word they will build new houses in the future.”

The two houses went to a property developer for a combined price of £2.96m, well above the reserve price. The squatters left and the former social housing was tastefully modernised by the new owners. The flurry of publicity around the sale of “Britain’s most expensive council house” set the tone for a 2015 Conservative manifesto pledge to force councils to sell their most pricey social housing properties and reinvest in new builds elsewhere. In an implicit reference to Park Street and other high-profile news stories from the same era, prime minister David Cameron spoke with astonishment about how some council homes in London had sold for more than a million pounds.

“1 in 200 million chance”

For the uninitiated, Omaze is an enormous financial success story that trades on the British desire for a home and the national faith in an over-inflated housing market.

It may look a lot like gambling, and smell a lot like gambling, but somehow it is not legally regulated as gambling. Instead Omaze is legally a “prize draw”. A minimum fee of £10 buys you 15 entries. To comply with the law and avoid being regulated as a lottery, Omaze has to let you enter for free if you send a postcard with your name on it to the company. Given second class stamps now cost 87p, more than the most expensive cost of a single online entry, you probably wouldn’t bother.

The company positions itself as a for-profit fundraiser. It buys a house and furnishings, markets it, and promises to donate millions of pounds from each raffle to a named charity. In the case of 21 Park Street the beneficiary is The King’s Trust, the monarch’s personal charity for young people.

Polling in April 2024 suggested around a tenth of the British public had either “definitely” or “probably” taken part in an Omaze draw in the last month. Yet Omaze’s unregulated status as a raffle, rather than a lottery, means it does not have to declare the odds of winning a house.

But there are ways to estimate the number of people taking part. Charities receive 17% of the ticket sales, with recent competitors raising more than £4m for each good cause. This would imply total revenue per raffle of around £25m per prize draw. If they were all sold at the subscription rate of 200 tickets for £25, this implies each individual ticket has a 1 in 200 million chance of winning. Even in the best case scenario for gamblers, where all the tickets were sold at the most expensive rate, the odds only drop to 1 in 37.5 million. The reality is that you’ve almost certainly got a far bigger chance of an individual ticket winning the jackpot on the National Lottery than winning 21 Park Street in this weekend’s Omaze draw.

“The current owners will be delighted to have gotten out”

But why is such a desirable London townhouse being offered up by Omaze at all? One possibility is that a townhouse in this area of London is not as desirable as the current owners had hoped.

Neal Hudson, a residential property analyst who runs the company BuiltPlace, suggested the other side of the 21 Park Street story is one of price stagnation in the high-end London property market. He said that since 2014 steep property taxes introduced by Conservative chancellor George Osborne and then Brexit have taken their combined toll and dampened demand for high-end homes.

In this telling, Southwark council offloaded the properties at the peak of the London market back in the early 2010s. You might not feel much sympathy if you’ve got no chance of getting on the housing ladder but in the world of £5m houses there’s not been much in the way of price growth, said Hudson: “That part of the market has really been stagnating for the past decade.”

What we do know is that, according to land registry records, after redevelopment 21 Park Street was sold in 2017 for £3.1m to local property developer Tom Sherwood and his knitwear entrepreneur wife Juliette, who have another home in the Cotswolds hotspot of Chipping Campden.

They subsequently listed it for sale in April 2023 at an asking price of £5m but failed to find a buyer. It was then listed again, with a variety of estate agents, all of which failed to shift it to a private buyer. Omaze, who did not disclose the price they paid for it, described it in their advertising as “worth over £4.5m” – although, as with any property, a valuation is only real when you find someone willing to pay that amount.

An Omaze spokesperson said they had used independent property experts to conduct an "extremely thorough" valuation that takes into account "a variety of factors". They also declined to comment on the property’s former status as a council-owned property.

“My gut instinct is that it’s quite a lot of money,” said Hudson. “It looks like a lovely house but it’s not in your core prime central London — Knightsbridge, Notting Hill — sort of market. It’s probably on the fringes of what someone would be looking for as a family home.”

If the Omaze winner wants to flip the property to someone else for £4.5m then they will also have to find a person willing to pay at least £453,750 in one-off stamp duty taxes.

Hudson’s verdict? "The current owners will be delighted to have gotten out and gotten a sale.”

“I have bought one, yes.”

Back outside 21 Park Street, the stream of hopeful visitors continues.

The area has changed enormously over the last decade; Borough Market is now an expensive street food centre and groups of Chinese tourists wander by with platters of lobster. A branch of the Barrafina restaurant group is mere yards from the front door. But on the other side of the street, Southwark council still owns a row of old Victorian houses. One of these was put up for auction last year at £1.1m, under plans by the borough to speed up the process of selling off high-value council houses.

Liberal Democrat councillor Chamberlain said he would support spending hundreds of thousands of pounds on modernising a single council house in the name of community cohesion: “The reason it would cost so much [to repair] is the council has failed to look after it over many decades. The problem with selling off homes that are worth more on paper is that they’re not going to get replaced in our community. It becomes another private home that exacerbates the existing unaffordable local market. The homes that the council says they will build with it aren’t being built.”

Chamberlain said the Omaze raffle for 21 Park Street tells us something deeper about the capital’s property market: “It does speak to how broken the housing market is that you can have people buying lottery tickets for a former council house. People are being poorly served by the current housing market and how we manage housing in London. Lots of normal people have no prospect of ever owning a good quality home in the borough.”

Yet there was one thing he had to add. The local councillor had, himself, bought a ticket for the raffle: “I’m ashamed to say I have! I’ve only bought one — that doesn’t give me a good chance. I have friends that have bought tickets as well. And I’ve got friends who have lived in Borough who rent a one-bedroom studio who have no chance of staying in Borough if they don’t win the lottery.”

He’s not the only local councillor to have done so. At the end of our chat, London Centric also asked Richard Livingstone, the Labour representative who oversaw the original sale of 21 Park Street and faced down the housing activist squatters, whether he was going to buy a ticket for the Omaze draw.

He replied: “I have bought one, yes. I saw it and I thought ‘blimey that would be a lovely place to live!’”

Did you appreciate this edition of London Centric? Please forward it to a friend, post it on social media, get in touch via email or WhatsApp, or leave a comment.

Between this, the mania for crypto currency, and young people all trying to win the influencer algorithm lottery, it feels like we've sleep-walked into a society where people believe the only chance they have at social mobility is gambling.

That does not feel... great.

I *loved* this piece but it tells us something just so totally depressing about the housing market in London. Rooting for Kim to win it!